I first came across the idea that great strengths can emerge from great constraints in Ryan Holiday’s book The Obstacle is the Way. He takes a philosophical and historical approach, citing numerous Very Important People in history who used their unique challenges as springboards.

I was annoyed by the idea, thinking something along the lines of “These examples must be cherry-picked.” It seemed too neat, too feel-good to be true.

But I recently read another book that continued the theme, A Beautiful Constraint (Affiliate Link), recommended as essential reading for any entrepreneur by Seth Godin. The book was written by Adam Morgan and Mark Barden, who run a marketing and branding agency called eatbigfish that specializes in helping “challenger brands” overcome incumbents in their industries.

The pattern they found was so consistent they wrote a book describing it: the very best place to look for breakthrough capabilities is right behind your biggest constraint.

A Beautiful Constraint has flaws. It sticks a little too closely to the standard business book template, ironically. But in the intervening years between these two books, I too have seen this pattern again and again, and I think it could have huge implications in the realm of individual learning and personal productivity. This summary is my attempt to make it into a building block for future use.

A Beautiful Constraint Summary

We begin with a barrage of examples. I’m not a fan of most business case studies, but they do set the stage:

- Mick Jagger’s unique dance style evolved due to the lack of space in the London nightclubs where the Rolling Stones played in the early days. He needed a way to be distinct and noticeable with no more than a few square feet of space.

- Google’s famously simple homepage wasn’t a brilliant strategic gambit. It was the product of Larry Page’s limited coding ability.

- Mario, the world’s most recognizable video game character, got his look from the limits of 8-bit graphics: a mustache and big nose because they couldn’t render facial expressions; a cap because they couldn’t do hair; and overalls because the body was just one big lump.

- Much of the intensity and thus popularity of basketball can be attributed to the time limitations imposed by the stop clock, which was introduced in 1954.

- When William Spaulding, the head of Houghton Mifflin, challenged Theodore Geisel (known as Dr. Seuss) to write a children’s book using a vocabulary of only 225 words, he responded with the classic The Cat In The Hat, which helped transform literacy education. When the head of Random House bet him $50 he couldn’t write a book using only 50 words, his answer was the even more successful Green Eggs and Ham.

What could explain this phenomenon?

It starts with the observation that we are living in an era of abundance, while also besieged with new constraints: we must produce cars that go faster, while also using less fuel; we must produce fast food that is also healthy; we must have higher farming yields, while also using less water; we’re asked to be ever more innovative, while company budgets tighten; we’re asked to live free and creative lives, while we have trouble paying the rent.

It seems that with every new abundant resource we’re given, we’re also handed a matching constraint.

But if you accept that a tradeoff must be made between these two poles, you’ve already lost. You’re already “inside the frame” of a scarcity mindset. And the most scarce thing in a world of scarcity is original thinking.

The people and companies that are thriving today are those that turn the tradeoff to their advantage, not the ones that compromise and make the best of things.

As Daenerys Targaryen, mother of dragons, always says:

“I don’t want to turn the wheel — I want to break the wheel.”

Nike was aggressively targeted for sweatshop conditions in the 1990s. They initially responded defensively, pointing out that these were the standards of their industry. But they quickly realized that their ability to respond quickly to these criticisms was a competitive advantage. Fast forward to today, they are spearheading research on non-toxic glues and waterless dyeing techniques, open-sourcing their findings to encourage the whole industry in this direction (while also gaining brand loyalty).

Simcha Blass, a farmer on an Israeli kibbutz, noticed that a leaky pipe made a tree grow much stronger than its neighbors. The arid conditions of the soil in that region exposed the possibility of drip agriculture. The lack of cheap labor on the kibbutz meant everyone had to pitch in, making them familiar with the process and thus able to suggest improvements. Political tension with neighbors forced them to grow crops that could survive export to Europe, which became a huge hit. Three constraints, three breakthroughs, to help make Netafim the $800 million dollar company it is today.

But what is the actual mechanism? What are the underlying principles of “constraints as opportunities”?

I had to hunt for small clues scattered throughout the book, but here are the candidates:

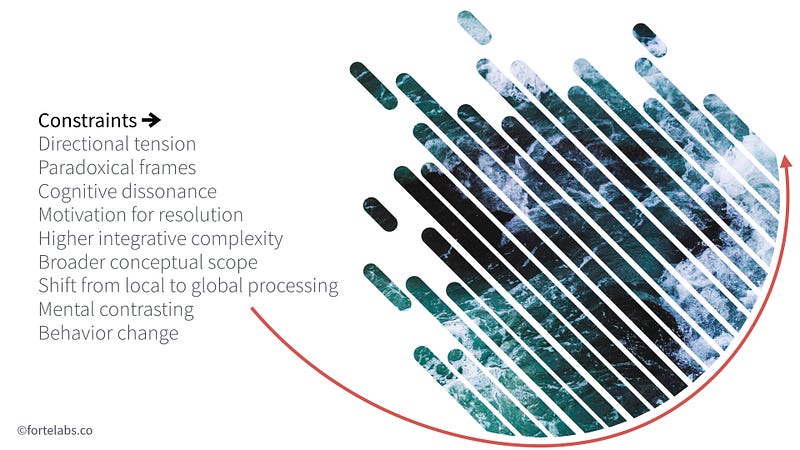

- Constraints provide boundaries for us to explore and push up against, focusing our energy and creativity on an unforgiving reality that is also limited in scope

- Constraints produce a directional tension, since they tend to be limits on moving in one direction, but not others, propelling us off well-worn paths

- Constraints introduce conflicting, often paradoxical frames (we want X, but also Y), which create a cognitive dissonance that we will work hard to resolve

- Constraints promote higher integrative complexity, broader conceptual scope, and a shift from local to global processing, expanding the space of possible solutions

- Constraints encourage mental contrasting (comparing the promise of future benefits with the inevitable future if nothing changes), which is a powerful driver of behavior change

The problem with abundance is that our mental machinery did not evolve for it. Flooded with opportunities and options, we lose the anchors and the stepping stones our evolution always assumed would be present.

As soon as we encounter a constraint, it seems that powerful subsystems in our brain come online, expanding and accelerating our thinking. Our challenge in the modern world is to move from a scarcity to an abundance mindset, while retaining the ability to strategically stimulate and redirect the primal capabilities dormant inside us.

Morgan and Barden outline a 5-step process for using these insights on real-life challenges, that I want to summarize here (with liberal interpretations) for you to try. It bears striking similarities to one I’ve been developing slowly over the years, and I’m excited to see the overlap:

#1 Raise your bold ambition

Instead of reacting to a constraint by lowering your level of ambition, which is what most people do, massively increase your ambition, such that all conventional approaches are unthinkable.

Bold Ambition x 10

#2 Create a propelling question

Combine the constraint and the bold ambition to form a propelling question, giving your search a shape and direction.

Constraint + [Bold Ambition x 10] = Propelling Question

Audi was faced in 2006 with the challenge of designing the R10 TDI car for the famous 24-hour Le Mans race. Instead of going directly to work on the implicit question behind any race — how do we build a faster car? — they asked a different question: How could we win Le Mans if our car could go no faster than anyone else’s? They linked a new constraint (going no faster than anyone else) with a bold ambition (to win the race).

As all the other teams obsessed over the constraints on pure speed, chasing diminishing returns and narrowing their scope, the Audi team went in the opposite direction. They introduced diesel technology for the first time in their cars, which allowed them to make fewer pit stops, which helped them win the race for the next 3 years.

Some other examples of propelling questions:

- How do we build a well-designed, durable table for five euros?

- How do we establish a stronger relationship with this buyer than the market leader, without a communications budget?

- How do we grow more and better quality barley using less water?

#3 Give the propelling question legitimacy, authority, and accountability

This question cannot be an idle concept. It has to be asked by someone with authority and legitimacy. By someone who will demand an answer, and cannot be refused.

In other words, humans don’t work without accountability. I’ve seen this take the form of promises to clients, deadlines and timelines, self-imposed penalties, or even something as simple as collaborating with others who will be let down if you drop the ball. Humans are capable of rising to any occasion, but only if the occasion demands it.

Constraint + [Bold Ambition x 10]= Propelling Question^[accountability]

#4 Identify undervalued resources

One curious effect of scarcity thinking is that we tend to overvalue what we lack, and undervalue what we have in abundance. The basic heuristic of scarcity causes us not to see even the resources we do have.

I constantly see people with immense knowledge and nearly superhuman skills, claiming they “don’t know that much” and insisting “no one would pay for that.” The superconnector who creates community wherever he goes doesn’t actually know the true value of intimate conversation, because he finds it everywhere he goes. How could it be scarce? The genealogy expert can’t imagine charging for the research skills she’s developed, because she does that research for fun on the weekends. Why would anyone pay her to do something so fun?

And the flip side is just as tragic: the particular skill you don’t have, is always precisely the one you think you need before getting started. The knowledge you haven’t quite learned, is always the “best” knowledge. That is, until you have it. Then it’s worth nothing.

This step entails looking for the resources we have in abundance, that we’re practically sitting on, and trading them for resources that others have in abundance. Look for your “productivity superpower” — the ability that is so abundant for you that it is effortless and fun. What to you feels like play will look to others like walking up vertical walls.

Effortless, Fun Capability = Abundant Resource

Is your audience tiny? That means it’s also more focused, more personal, more intimate. Those qualities are resources that others will gladly barter for access to.

Is your skill difficult to package up? Great. That means you’ll have few competitors, can charge premium prices, and no one will be able to copy it. Find someone in need of those things to trade with.

Is your knowledge not written down or captured anywhere? Good. You’ll be able to share the process of doing so as a case study, which will make you more relatable. Find someone who’s dying to learn what only you can teach, and make an exchange.

Do you hate technology? Wonderful. You’ll have to rely on things like drama, charisma, service, and vulnerability, all far more powerful than any mere device. Find one of the many people who are brilliant with technology but don’t have people skills.

Do you have no experience? Perfect. You’ll be unburdened by years of baggage and outdated paradigms. Which grizzled veteran is starving for a bit of your innocence, enthusiasm, and fresh eyes?

Have you never done anything like this before? Then you are unburdened by the legacy and inertia that any successful person battles every day. Your center of gravity is at the cutting edge of the here and now, whereas their impressive past weighs them down.

Being resourceful is not about owning or controlling lots of resources. It is about accessing resources without having to own them, by relying on the relationships, the networks, the communities, and the organizations you’re already a part of.

When you don’t have resources, you become resourceful. — K.R. Sridhar, Bloom Energy

#5 Write a “We can if…” (WCI) statement

Now combine the propelling question with the new resources you’ve identified, to form a “We can if…” statement. This statement turns the tradeoff you’re faced with inside out, making the constraint itself a component in its own solution:

Propelling Question^[accountability] x Abundant Resource = WCI Statement

- Airbnb: we can offer great photos of each accommodation (bold ambition) without the personnel and travel overhead of staff photographers (constraint) if we use other people’s skills as photographers; people from within our community (resource)

- Duolingo: we can translate the web into other languages (bold ambition) if we get a million people to do it for us (resource). And we can get a million to do it for us, if we help them learn a new language while they’re doing it (constraint)

- Unilever’s value detergent, Surf: we can offer a more appealing cleaning promise (bold ambition) if we introduce fragrance and sensory delight as emotional rewards for cleaning (resource), over and above functional effectiveness (constraint)

- Food trucks: we can afford to start our restaurant business (bold ambition) if we substitute the high costs of a permanent fixed location (constraint) with the possibilities of a smaller, more mobile one (resource)

- Rent the Runway startup: we can create access to the world of couture (bold ambition) for young women unable to afford the prices (constraint) if we build a rental model with inventory provided by the fashion designers themselves (resource)

This last step is where the real creativity lies, and where no simple checklist will help. It requires powers of perception: seeing the fit between the three elements that countless others have not seen. It requires granting yourself a radical level of self-trust, to be so bold.

The implications

When I started self-employment 4 years ago, it wasn’t because of a bold ambition to change the world. It was a chronic illness that was slowly making it impossible for me to work a standard 9–5 job. It slowly became clear that I would never be able to climb the corporate or any other ladder in the usual way. One reason I am so passionate about using technology to empower people’s productivity is that I shudder to think how few opportunities would be open to me without technology at my disposal.

Looking back, I think this illness is the only reason I had the courage to take such a risk. Failure simply wasn’t an option, because I had nothing to fall back on. And I’m surprised to see that I accidentally followed this process: I increased my ambition (to create a fulfilling and impactful life); I linked this ambition with my constraint (needing to work on my own schedule and pace) to create a propelling question (How do I author a fulfilling and impactful life while preserving my health and happiness?).

The undervalued resource I found was personal experience and empathy with the limitations on traditional ways of working. Talking to many people about my condition, I discovered that nearly everyone has something similar: they have a condition that needs care, a loved one who has a condition that needs care, or the way they think and work just doesn’t fit into the standard template. For others, they want to do something that doesn’t earn enough money to live in an urban center, or simply want more time for family, friends, and enjoying life.

Our current paradigm of work is the fundamental constraint on all these desires. So my goal is to invent a new one. This is my new bold ambition, which I am linking with a new constraint (I am only one person) to form a new propelling question: how can one person invent a new paradigm of work? With the help of your accountability, I’m being propelled toward a new possibility: “We can invent a new paradigm of work if I focus on training people in the productivity meta-skills they’ll need to invent it for themselves.” My undervalued resource is you.

What if constraints on individuals were not unfortunate circumstances, or bad strokes of luck? What if they were not the barrier to what we want in life, but the very gateway to it? What if physical disabilities, tragedies and traumas, fears and insecurities, living in a developing country, not having money, not having connections, not having experience, etc. were all great opportunities to channel resources in unique ways?

If that were true, we would instantly enter a world of abundance, because there is nothing more abundant in the world than limitations.

Seeking and leveraging constraints is not easy, but let me offer you a little mental contrasting in case you need the motivation to try it. Research shows that a mind confronted with too much work exhibits the same characteristics as someone who lives in poverty. A constant lack of bandwidth, lack of time, and lack of hope in the work that dominates our waking hours makes us less insightful, less open-minded, less forward-thinking. We adopt the tunnel vision of someone just surviving for tomorrow, unable to see the diamonds in their begging bowl.

And 70% of employees say they have no time for creative or strategic thinking.

Constraint-Breaking Workshop 9/8/17

Turning constraints into opportunities is not easy. That’s why branding and design thinking workshops are very expensive.

But I want to try an experiment: I’m going to make our next Praxis Town Hall (on Friday, Sept. 8 9–10am PDT) a “Constraint-Breaking Workshop.” I’ll choose 2 people to present an intractable problem they’re facing, and as a group we’ll follow the process outlined above, putting our heads together to produce a breakthrough solution in a constrained amount of time. I’ll also invite the graduates of Building a Second Brain, to see if they can help us apply those techniques to the problem.

Register for the workshop here to get a calendar invite and, if you can’t join using the Zoom videoconference app, the confirmation email will also contain telephone call-in details (U.S. toll and international).

Come prepared with “impossible” problems.

Follow us for the latest updates and insights around productivity and Building a Second Brain on Twitter, Facebook, Instagram, LinkedIn, and YouTube. And if you're ready to start building your Second Brain, get the book and learn the proven method to organize your digital life and unlock your creative potential.

- POSTED IN: Book summary, Books, Creativity, Emotions, Entrepreneurship, Strategy