I’ve become obsessed with coaching.

It started in February, when I started the 4-month Self-Expression & Leadership Program at Landmark. I was assigned an accountability group and a coach, who guided me through the process of planning and executing a community service project. That process included learning how to communicate a vision, how to recruit others into it, how to share authentically and vulnerably, and many other skills not taught in any school.

I got so much out of the program that I decided to volunteer as a coach in the next group. I’ve been working with my small group of 5 participants for 2 months, and it’s been one of the most rewarding experiences of my life.

I started looking for opportunities to be coached in every area possible. I joined a Crossfit gym, committing to the smallest class available so I could get as much individual attention from the coach as possible. I hired a voice and speech coach, to help me with some bad habits I’d picked up over the years. And I joined a 3-month holistic health coaching program, combining Chinese medicine, reiki, therapy, feng-shui, and acupuncture (I know, I know, so California).

What I’ve found has been remarkable: a new level of performance and enjoyment, far in excess of the investment I’ve put in. I’ve tried to shift as much of my consumption (of products, services, and information alike) as possible to coaching and accountability groups. This shift has convinced me that the fundamental bottleneck in nearly every area of my life is not knowledge, but accountability.

I plan on sharing as much of what I’ve learned in these programs as possible, but I wanted to start by sharing a summary of a book that has given me a lot of clarity on what coaching is and what it’s intended to do.

The book is called The Inner Game of Work (Affiliate Link), by Timothy Gallwey.

Gallwey is much better known for his first book, The Inner Game of Tennis. In that book, he lays out a simple but powerful new framework for not only coaching, but also teaching and learning.

That framework starts with the idea that our efforts to improve ourselves and our performance often end up interfering with that very performance.

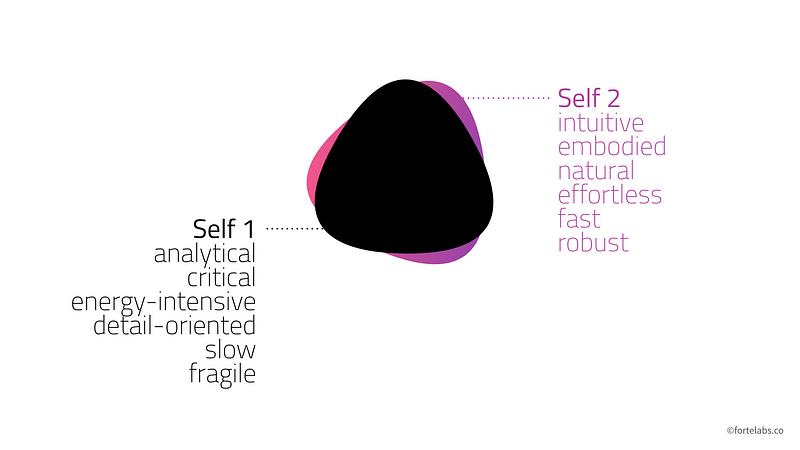

What he calls Self 1 (the critical, analytical self) tries to control every little thing, like a tennis player gripping the racket too tightly and trying to force every part of his body to move “correctly.” Traditional coaching — often focused on correcting individual movements or flaws in isolation — actually makes this worse, as it removes responsibility for learning from the student to the coach.

Gallwey’s approach to coaching is very different: to calm Self 1 using focus, so that Self 2 (the intuitive, embodied self) can come to the forefront and take control. He doesn’t give “instruction” — he shapes the student’s awareness. He might ask them to pay attention to the stitches on the tennis ball as it flies through the air, or pay attention to the exact moment when the racket hits the ball, without trying to actively correct it. With Self 1 thus fully occupied, Self 2 is free to emerge.

Non-judgmental awareness to a few key variables can cause a player to make profound improvements very quickly, in an integrated and embodied way. This famous video of a complete novice learning to play tennis in 10 minutes using this method is the best testimonial:

The Inner Game of Tennis revolutionized the coaching of tennis, golf, and other sports, and is well known throughout the world. But Gallwey later elaborated his method into a framework for all kinds of learning and performance, using a key insight:

We learn faster when we pay attention and see the world for what it truly is, not for what it should have been.

Self 1 is just as present in our work, micromanaging every little thing we do, as in sports. Self 1 introduces distortion into every action we take, which leads to a distorted response, which confirms the original distortion. Traditional productivity advice focuses on behavior — the worker’s response — without ever dealing with the root problem: the original distortion in perception.

Letting go of Self 1 and exercising trust in Self 2 feels like you are losing control, but in fact you are gaining control by letting go of an inferior means of control.

The role of the coach is not to provide content, solutions, or advice. It’s not to help, fix, or answer. The coach’s job is to hold up a mirror to the client’s own thinking, including how their attention is focused and how they define the key elements of the situation. The client can just start thinking aloud, allowing the coach to “eavesdrop” on the conversation. That is why the conversation can move quickly — the client is relieved from having to brief and then update their coach on all aspects of the situation, and much more importantly, it doesn’t invite a shifting of the responsibility from client to coach.

More specifically, the coach leads the learner through three conversations in sequence:

- Conversation for Awareness: knowing the present situation with clarity

- Conversation for Choice: moving in a desired direction

- Conversation for Trust: accessing one’s own inner resources to make the change

Let’s discuss these one at a time.

The Conversation for Awareness

This first conversation is meant to answer the question: “What’s happening?”

It invites the following types of question:

- What stands out?

- What do you notice when you look at x?

- How do you feel about this situation?

- What do you understand about x? What don’t you understand?

- How would you frame the underlying problem?

- How would you define the task?

- What are the critical variables in this situation?

- How do they relate to one another?

- What are the anticipated consequences of x?

- What standards and timeframe have you accepted in this task?

- What has been working? Not working?

The coach draws out the implicit interpretations, beliefs, and assumptions governing how they see their reality.

The Conversation for Choice

The primary purpose of this conversation is to remind the client that they have mobility, which Gallwey defines in this context as reminding them that they “have the capability of choice and can move in the direction of their desired ends at any time.”

If Awareness is about “what’s happening,” then Choice seeks to answer “What do I want?”, using the following kinds of questions:

- What do you really want?

- What do you want to achieve?

- What are the benefits of x?

- What would be the costs of not pursuing x?

- What would it look like in y weeks, months, years, from now?

- What don’t you like about those ends?

- What would be a fulfilling means of getting there?

- What changes would you like to make?

- What do you feel most strongly about in this situation?

- Who or what are you doing this for?

- How does this fit in with your current priorities?

- Do you have any conflicts about this course of action?

- What would success in this endeavor mean to you?

- What alternative possibilities can you consider?

And the most common one: Why would you want to do that?

The coach’s job in this conversation is to sense the underlying commitment of Self 2, which is always in touch with our deepest desires, and not buy in to Self 1’s limited conceptions of what is possible. The goal is to carefully separate the agenda of our own desires from the agendas of “others in us.”

The Conversation for Trust

The most important outcome in coaching is that the client ends up feeling respected, valuable, and capable of moving forward. At every turn, the coach seeks to avoid undermining the trust they have in themselves by inappropriately becoming an answer-giver, problem-solver, or judge.

These are some of the questions that can be used:

- If you could do it any way you wanted, how would you go about accomplishing this task?

- When have you succeeded in a challenge similar to this one?

- At your best, what qualities, attributes, capabilities, do you bring to the situation?

- Direct acknowledgment by the coach of some of the above

- Where could you find the help you need to accomplish this task?

- What’s the most difficult aspect of this task?

- What is your understanding of this situation?

- What first steps do you see?

- How comfortable (confident) do you feel about doing x?

- What would it take to make you feel more comfortable?

- What did you like most about the way you accomplished this task?

Since trust in oneself is natural in children, the goal of this conversation is to help the client “unlearn” the doubts, fears, and limiting assumptions that have accumulated over time. This is the most delicate, but also the most important conversation. The coach offers the gift of trusting the client more than the client trusts themselves, granting them the recognition and confidence to make a move.

Focus

At the very heart of the “inner game” approach is focus. It is only when we are giving our full attention to something that we can bring all our resources to bear effectively.

Why?

Because it is only when we are giving full attention, that self-interference (embodied in Self 1) is minimized. We don’t minimize self-interference so we can then focus; we focus so we can minimize self-interference. In the fullness of focus, there is no room for Self 1’s neurotic fears and doubts.

Focus is easier to sustain when you are doing something you’ve freely chosen to do. In this sense, focus is not just a skill you develop by learning a technique. It is an emergent phenomenon that arises naturally from your motivations being aligned behind what you are doing.

Desire

What is rarely appreciated about focus is that it is governed by desire.

A pickpocket focuses on the purse or wallet. The lover is always oriented toward the loved one. A trout fisherman doesn’t have to “try to focus,” any more than a cat has to try to focus on a dangling string. A person in the grip of fear will notice whatever is frightening. An angry person will notice whatever is making him angry.

In our pursuit of focus, then, our choice is over which desires to nourish, and which to starve. Nourishing the desires of Self 2 builds stability and self-fulfillment. Nourishing Self 1 desires strengthens self-interference, inner conflict, and distraction.

Here’s what makes it difficult: if you use Self 1 to control Self 1, you strengthen the very taskmaster that is causing the conflict. Self 1 has the upper hand any time it convinces you either that you need its advice, OR that you need to fight it into submission. In either case, it succeeds at its goal: to stay in control.

If instead you acknowledge Self 2 and its perfectly natural desires, you can reach for it and give it whatever attention you have at your disposal. A little attention is withdrawn from Self 1, diminishing its influence, which in turn gives you greater access to Self 2.

But accessing one’s true desires is also not easy. Often people won’t allow themselves to get in touch with what they truly want unless they already see the means of achieving it. Or their desires are colored or completely dominated by the desires of others for them. This is why some people find it impossible to figure out what they want.

Here are some useful questions for identifying desires:

- How clear are you about what you want?

- What do you really want?

- How connected do you feel to your passion, to the wellspring of your desire?

- Have you ever felt more connected? When, and to what? As you look at your different desires, do they seem to be aligned or to be pulling in separate directions?

- Where do your desires come from — thought or feeling?

- How clearly can you distinguish your desires from the expectations of other people?

- To what extent do you feel you are “steering” your desires versus being driven by them?

- Do you feel free while working?

- What does being free mean to you?

- Do you desire to be free?

- How do you know?

Most of us were brought up with the idea that our desires are fundamentally untrustworthy. Ideals are trustworthy. Reason is trustworthy. Desires are suspicious, because they pull us away from our ideals.

Of course, no one ever explained where we were supposed to get the desire to pursue the ideals. The implied motivation, of course, was fear — fear of not being accepted, fear of not being successful, fear of not surviving. All our ideologies, from conservative to liberal, religious to atheist, are in agreement: human nature is bad and needs to be controlled from the outside.

These external, fear-based methods of control are internalized and become our Self 1, the judge of both our desire and behavior. Strengthening our Self 2 requires granting our desires and ourselves a radical level of self-trust.

A new definition of work

Gallwey’s philosophy implies a new definition for work: the process of growing your capabilities while in the process of producing results in order to be better able to produce future results.

Learning, personal growth, and performance are all just parts of the same feedback cycle, each feeding the others.

What this definition recognizes is that our desire to learn is as fundamental as the desire to survive and to enjoy. We don’t just work; we are changed by the way we work. We develop qualities as well as skills. New intellectual, emotional, creative, and intuitive capacities are developed through our work experiences. Determination, courage, commitment, empathy, imagination, and many communication skills are all at play. We may not see this learning while in the midst of our labor, but in retrospect we can tell it has occurred.

What fuels this feedback cycle is enjoyment. And there is one critical variable underlying enjoyment at work: the worker’s relationship to themselves. To the extent I value myself, my time, and my life, I will not allow myself to work in a state of misery. Enjoyment of every moment becomes an important priority, no matter what I’m doing. I have to ignore the indoctrination that told me this was selfish.

The most important thing to pay attention to then is how you are honestly feeling during any segment of your work experience. And using that awareness, to reflect on what contributed to the enjoyment or lack thereof. To give simple awareness a chance, before rushing in to “fix” the situation. Gallwey says we might be surprised to find the extent to which awareness by itself is curative.

In my experience, that’s an understatement.

Freedom

It is easy to lose sight, in the midst of all these details, of the bigger picture here. What we want is nothing more than to work free.

What we seek is not “freedom from” our responsibilities and commitments. Those things give us life. It is “freedom for.” Freedom for enjoyment, freedom for harmony, freedom for purpose.

There are those who enjoy working. But what they are really enjoying is themselves while working. They make a distinction between themselves and the results of their work. This distinction brings a detachment that allows for enjoyment independent of circumstances.

The good news is that Self 2 is always and forever biased toward enjoyment. We like feeling good. It is biased toward living harmoniously with others. We always have access to these things, as soon as we give up some of the Self 1 demands for approval, recognition, and ego.

Resistance to change is often resistance to the process of change, rather than the particular change at hand. The key is to understand that we are always changing, all the time. There is no static, stable ground. The person who works out of fear will move toward fear. The person who works out of responsibility to family will move toward family. The person who wants to enjoy his life while working will move in the direction of enjoyment.

Working free means that I am growing in my capacity to fulfill myself. It means that I continuously increase my capacity to enjoy my life both when working and when not working.

Freedom in this sense is not satisfied with being in any flow. It must be the flow of our choice, heading where we want to go.

Follow us for the latest updates and insights around productivity and Building a Second Brain on Twitter, Facebook, Instagram, LinkedIn, and YouTube. And if you're ready to start building your Second Brain, get the book and learn the proven method to organize your digital life and unlock your creative potential.

- POSTED IN: Attention, Book summary, Books, Coaching, Flow, Goals, Personal growth