I’ve published a few ebooks over the past year, and have plans for a couple more before the end of the year. In contrast to fears about the “end of reading,” my self-publishing experiences have led me to believe that we’re in the midst of a transformational revolution in reading.

But it remains to be seen whether ebooks in particular will fulfill their potential in the digital age, or remain a mediocre one-time experiment. In this article I’ll examine the promise and potential of the modern ebook to try and see where we’re headed.

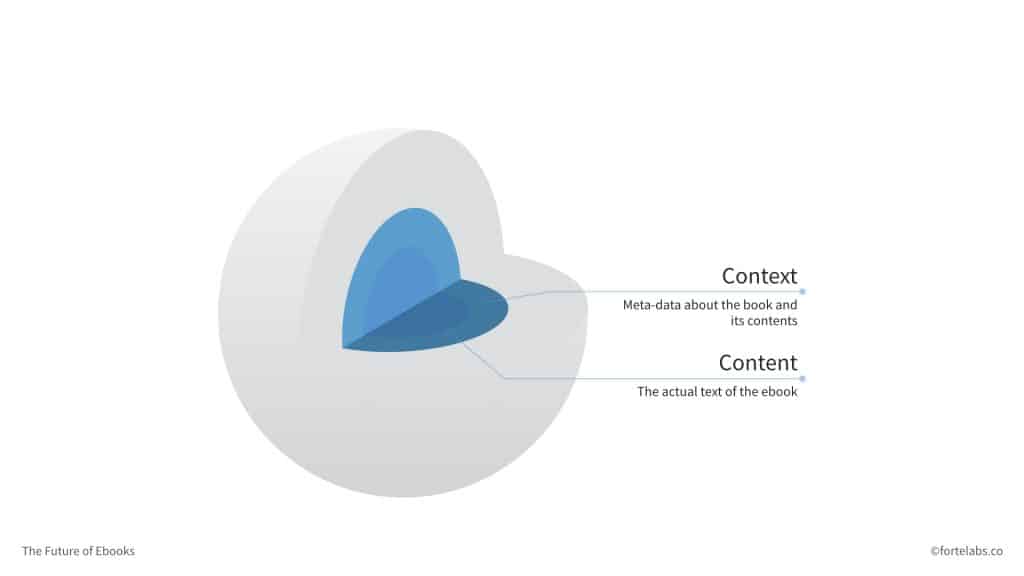

Context over content

The first trend that’s becoming increasingly clear is that content is a commodity. With ever-greater volumes of every kind of writing – articles, social media posts, blog posts – being created every year, with instantaneous global distribution via the internet, any business model based on content scarcity will no longer work.

As the emphasis shifts to discoverability amidst an endless sea of content, the focus for both publishers and consumers is moving to the context surrounding the book.

The context of a book – the metadata that describes what it is, what it’s related to, what others are saying about it, what it means, how it’s structured, how it was conceived, and countless other characteristics – has become paramount. Because without metadata, a book is invisible.

In the physical world, a lot of this context came “built in.” Bookstores, booksellers, librarians, and reviewers provided commentary and direction to help us find what we were looking for. The tiniest details of a book’s size, shape, cover design, title, inside flaps, and placement in the store gave us rich contextual clues.

But in the digital world, a lot of that is stripped away. There is no chance that you will serendipitously come across a book on the shelf, in the aisles, or at a coffee shop being read by someone else. You can be looking over someone’s shoulder as they read their Kindle and still have no idea what they’re reading! The signposts and markers of what is worthy of our attention have instead been funneled through personalized algorithms online. But algorithms cannot capture every possibility of what we might benefit from reading.

The challenge of digitizing books has never been the text conversion process. That is trivial. The hard part is rebuilding the socio-cultural context that used to so strongly shape our reading habits. Online marketing funnels, recommendations from friends, top seller lists, and other promotional tools have arisen to meet this need, but they don’t quite integrate into our daily lives as seamlessly.

Looking at new media and social networks, we get a strong picture of what context-first content looks like. Fledgling media startups start with context, asking where and why and how a person might want to consume media, and then they walk backward from that to create the perfect product and environment for it.

Snapchat developed disappearing selfie videos to meet the needs of teens seeking low-cost self-expression, while retaining their privacy. The recently announced IGTV is specifically designed for long-form, vertical video, capitalizing on the ease of hitting “record” on smartphones, while still giving video producers exposure through the Instagram network of 1 billion users.

While old-school publishers think of the internet as a new means of distributing the same old text containers, and software as a way to drive down costs, startups are building new kinds of content that couldn’t previously be conceived of. For them, text is one possible output of a channel, not the input.

What might it look like to create ebooks that focus primarily on adding context around the content? Here’s some of my favorite ideas I’ve come across:

- Show a heat map of the text, going beyond Kindle’s “most popular” passages to show the most hated, the most disagreed with, the most impactful, and other filters

- Allow readers to curate whose highlights they see: their friends, their neighbors, their colleagues, or influencers they follow in the relevant field

- Reveal data about the behavior of other readers (not just average reading time): How far does the average person get before giving up? How many notes do they take on each chapter? How many passages do they highlight? Which chapters do they come back to reference the most? Which passages are copied the most? How many people have followed each link?

- Enable deep linking into specific chapters, passages, or sentences, allowing visitors to see a short preview of the pages before and after, and purchase the book if they want to read more (this preview feature is akin to Amazon’s Look Inside, but without linking)

- Make the references and bibliography more interactive, allowing sorting by importance, relevance, date created, or other criteria for those seeking to dive deeper

- Reveal the writing process, including early sketches, a changelog, or editor’s notes, for those interested in exploring how the book was created

- Create tagging systems, either for idiosyncratic individual use or collective collaboration, to allow humans reading the text to add labels and hooks of semantic meaning for themselves and others

Digitizing text created great abundance. It is metadata, and the sorting, filtering, and searching it enables, that will help us make sense of it all. Metadata is the lens that makes our choices about what to read meaningful.

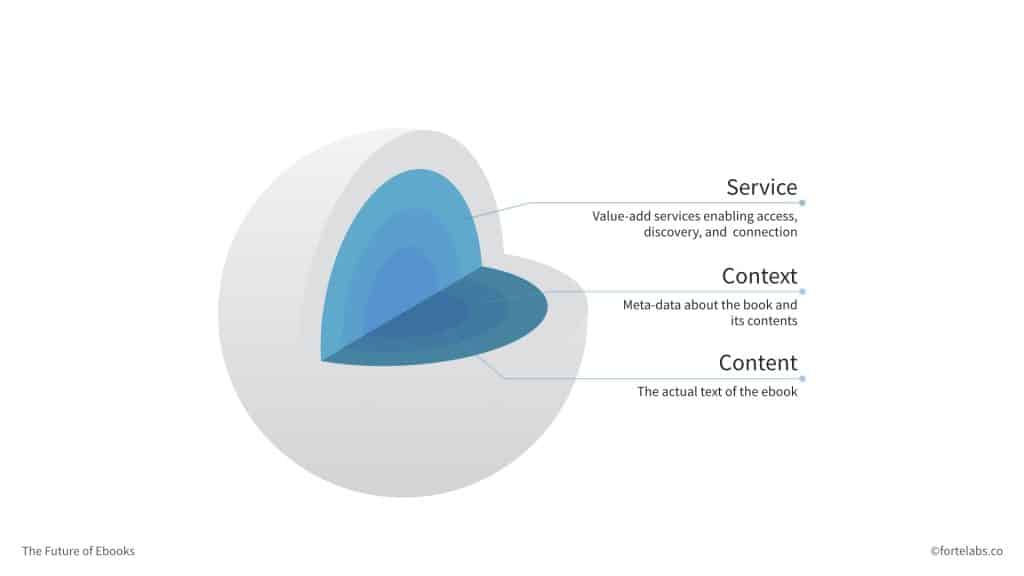

Service over product

If you zoom out from the ideas above, a new definition of “publisher” starts to come into focus. Publishers are no longer product companies. They are service companies. What matters is not the container wrapped around a bunch of exclusive text, but the service wrapped around the container. Context is paramount, but it takes a lot of work to organize and deliver it in a user-friendly way.

This is happening across the media landscape. Take iTunes as an example. If content was truly differentiated, the amount you paid would vary a lot based on quality. But it doesn’t. Every song costs 99 cents. The only reason people would pay the same amount of money for goods of vastly different quality is if it isn’t the product that matters, but the service that iTunes provides: on-demand listening across different devices.

The Kindle store has grown to dominate the ebook publishing market by offering a similar service: on-demand reading on any device. You don’t have to worry about where to buy it, how to get it, or where to store it. It’s essentially streaming for books, even if you never sign up for Kindle Unlimited, their all-you-can-eat service. The book is called when summoned, and Amazon takes a minimum 30% cut to ensure the stream never gets interrupted.

What are the services that readers want around their books? They want convenience, specificity, discoverability, ease of access, and connection. In a world where e-reading devices are ubiquitous, e-reading software is free, storage is plentiful and virtual, and any kind of content can be distributed everywhere at the push of a button, it is these value-added services that will define what is worth paying for.

Publishers need to realize they are no longer in the content production business. They are in the content solutions business. Their books need to become part of a value chain that solves their customers’ problems. Because what people ultimately want is not a book. They want an answer, a pathway, or a spark of insight that leads them to an outcome.

This implies a 180-degree pivot in how they treat their content. Instead of locking down written works with expensive and complicated DRM, publishers should adopt open, accessible, interoperable standards. They should use as much of the content as possible to build up context, and then use that context to promote discovery. Instead of competing on cost in a market that has zero costs, they should actively encourage every kind of reuse of their intellectual property.

The publishers that win in the digital age will be those that offer metadata and tools that help their readers manage the true enemy of reading: the curse of abundance.

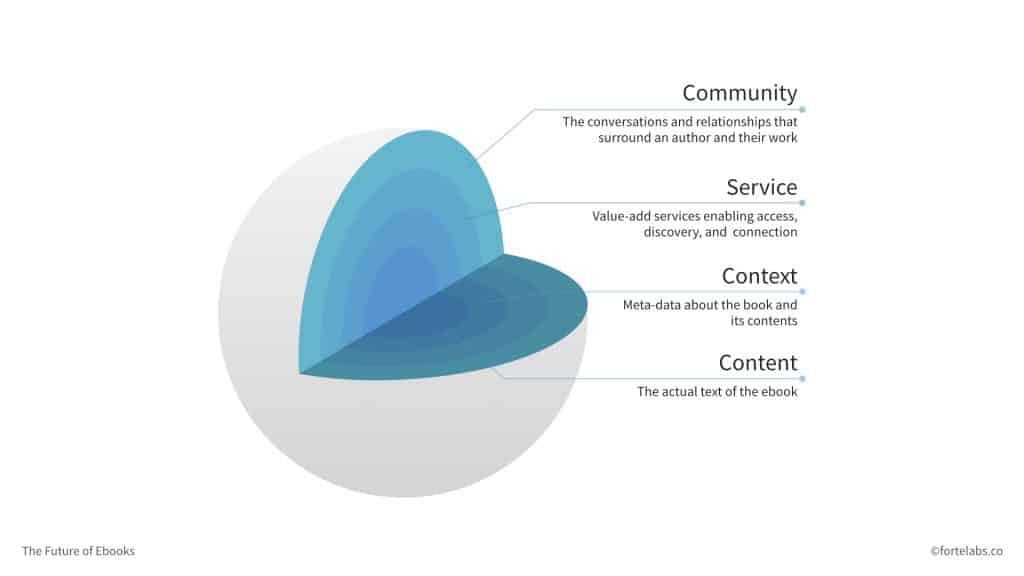

Creation over consumption

Underlying both of the trends above is a deeper one: people are moving from passively consuming content, to interacting with and creating it.

It now feels strange to many of us to sit on the couch and watch a TV show from beginning to end. What feels natural is to have our phone in front of us, posting on social media, commenting on others’ posts, and looking up actors, characters, and explainers.

In a way, this has always been true. Books have always called out to be annotated, marked up, underlined, dog-eared, summarized, cross-referenced, shared, loaned, and talked about. From the very beginning, books were social objects, pulling into place around themselves everything from book fairs, to book clubs, to writer’s circles, to conversations around the water cooler.

What’s changed is that all that marginalia – the bookmarks, notes, highlights, progress markers, reviews, comments, discussions – once hidden amidst the pages on each of our private bookshelves, has been published and networked online as digital artifacts. They reflect an individual’s preferences and intentions and take significant human attention to produce, which makes them valuable. In isolation, they are valuable to ourselves and perhaps our closest friends. At scale, the patterns they contain hold immense value as signals of insight, quality, and buying behavior.

Readers today expect to be able to “look under the hood” of a piece of content they’re consuming. They expect to be able to leave impressions on the medium, pushing and pulling and capturing the parts that resonate the most. For the works we fall in love with, we want to see how the sausage is made, so to speak, like watching the outtakes or director’s commentary for a movie.

Forward-looking publishers will begin to provide richer forms of interaction:

- Export individual metadata, like highlights and notes (going beyond the rudimentary export options currently offered by Kindle and iBooks to include images, different formats, and different destinations)

- Forking or editing the story (like video games or “Choose Your Own Adventure” stories)

- Add their own interpretation or expression (like adult coloring books, which have soared in popularity in the last few years)

- Mix and match pieces of content to create their own works (like Instagram Stories, or textbooks that allow professors to curate exactly the sections and chapters they want, to be printed on demand)

- Centralize discussions around the book (on Amazon or Goodreads even), with strong tools for surfacing the most useful or insightful comments and reviews

- Make ebook formats more HTML-compatible (EPUB, the most common format, is already just a specialized type of webpage), which would allow multimedia embedding and other sophisticated user interface features

- Include appendices or links to primary source material, deep dives on ancillary topics, and bonus extras like interviews or study guides, either free or paid

This level of interactivity might seem challenging, but it’s been done before. ChessBase is a database and book engine used by serious chess players around the world. Both ebooks (by multiple publishers) and mobile apps integrate directly with the database, which contains thousands of historical and modern games that can be searched and replayed. It includes a chess-playing engine so players can “step into” famous matches, allowing them to test their skills against the likes of Bobby Fischer or Garry Kasparov. It goes even beyond that, allowing players to author their own ebooks in EPUB and MOBI, including things like chess positions and tactics puzzles, from within the same interface.

Although there is clearly quite a bit more to ChessBase than an ebook, it points a potential way forward: ebooks as just one entry point into an ecosystem of content, services, apps, trainings, communities, and other products.

Streams over containers

What is at the heart of our desire to create is connection. As sublime as the creative process can be, what we’re truly after is what it evokes: surprise, delight, gratitude, insight, revelation. A reaction of any kind, really.

This too has always been part of the experience of reading. There is something special about meeting someone who has read the same book as you. You have something in common, something shared. The most mundane aspects of publishing, like taking pre-orders or posting a review, become special moments of contribution and belonging for the community that has gathered around an author.

Finding and downloading a book is easy, but getting it attention is harder than ever. This means that the network around a book will grow in importance, because without it, the book will never be discovered. And there’s no reason that this network should limit itself to “post-publication.” In fact, there is no such thing as “post” anymore. A book is a continual process of research and refinement, and readers have been injected much earlier into that process than ever before.

Books have been crowdsourced and crowdfunded, collaboratively edited, published one chapter at a time, and made into interactive webpages. The book is really just an excuse to form a community, which provides not only a pre-qualified market of committed readers, but a tribe of evangelists and promoters in the all-important channel of word-of-mouth.

It has become clear that the book is more of a social artifact than ever. The point-in-time contents inside a black-box container has been unfurled into a stream, an ever-changing conversation around the book, what it means, and why it matters. Time itself starts to become an essential ingredient in the writing – when and how often you engage influences your experience as much as the text itself.

Like Wikipedia, what’s most interesting is not the article itself, but the talk page, where the community hashes out its priorities and conflicts. The work’s authority comes from its responsiveness and shared intent, not its preciousness.

Imagine a future where instead of lending someone a book, you lend them your bookmarks – the notes, annotations, and references you’ve added. What you are really sharing is a collective conversation, the cumulative strata of many layers of marginalia built up through the skillful application of attention.

By connecting these small, local networks forming around each book, we could eventually create a single networked literature. Such a macronetwork would allow us to trace the source of any idea, concept, or influence through time. As Kevin Kelly puts its, “we’ll come to understand that no work, no idea, stands alone, but that all good, true and beautiful things are networks, ecosystems of intertwingled parts, related entities and similar works.”

Ebooks as digital artifacts

Streams are powerful, but they underestimate the value that humans place on tangible artifacts.

This is true more broadly of all things digital. As everything gets turned into a streamable, on demand monthly subscription, we are beginning to realize that the “things” we once surrounded ourselves with served purposes beyond pure utility.

As more and more of our lives take place online, there’s a growing disparity between our experiences, and the records of those experiences. The “souvenirs” that naturally accumulate in the real world aren’t guaranteed in the digital world. Data gets lost, devices get stolen, and photos and songs get trapped in obsolete formats. These souvenirs once functioned as touchstones, memory aides, and visual quantifiers, reminding us serendipitously who we are and where we’ve been.

The blessing of digital reading is also its curse – it is traceless. What came of those hours of precious attention we spent immersed in the mind of another? What did we take away from the experience, besides a warm fuzzy feeling of edutainment?

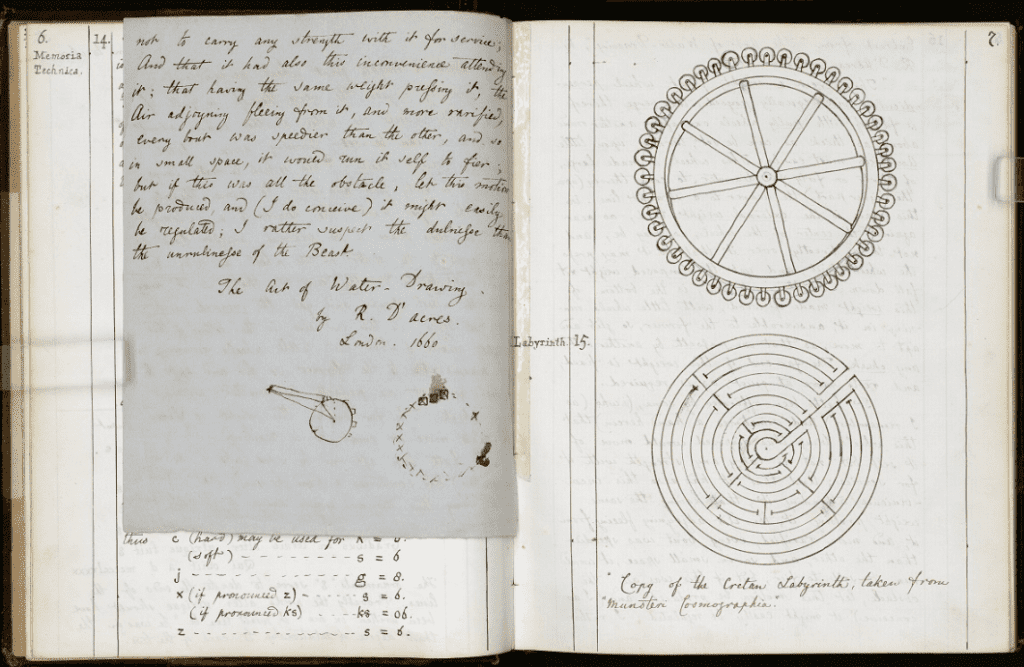

The hunger for artifacts will ensure that printed books continue to survive far into the future, and other more whimsical efforts like Bookcubes can help fill in the gaps. But the more fundamental need to take away something tangible from the experience of reading is one of the things driving the return of commonplace books – personal, curated collections of facts, insights, musings, quotes, and research originally invented in 19th century Europe, as a way to deal with the information explosion of the Industrial Era.

My online course Building a Second Brain is about how to create a “digital commonplace book,” meeting the need described by Craig Mod:

“There is a gaping opportunity to consolidate our myriad marginalia into an even more robust commonplace book. One searchable, always accessible, easily shared and embedded amongst the digital text we consume. An evocation — the application of heat to the secret lemon juice letter — of our shared telepathy.”

The book will endure

Considering all these major changes, I believe that books will endure. Publishing isn’t unprofitable; it’s unprofitable to use expensive workflows for a single use and a single format.

The field of technical writing has long offered a solution: single-source databases with multiple output capability. This is exactly how the internet works: Yelp keeps all its data in a database, whose contents can be served up to any number of devices in just the right size and shape desired. The risk of not publishing content in open, accessible formats will grow as the number of opportunities for reuse grows.

Kevin Kelly defines the book nicely: “A book is a self-contained story, argument or body of knowledge that takes more than an hour to read. A book is complete in the sense that it contains its own beginning, middle, and end.”

This definition starts to boil it down to its essence: a book is now best understood as a concentrated unit of attention.

Facts are useful, ideas are interesting, and arguments are important, but only a story is unforgettable, life-changing even. Only stories reach through to our empathy and our humanity, allowing us to walk a little in someone else’s shoes. To the extent that the grand challenges of our time require us to come to mutual understanding, and I believe they absolutely do, the book will endure as the minimum amount of concentrated attention required to become immersed in a story.

What a book transmits is not just information, but imagination. By crystallizing our ideas in the form of text, they take on a form that can survive years, decades, even centuries. Books free us from the bounds of time, like interstellar spaceships prepared to travel light years to find a suitable home.

I drew heavily on these sources for this article, but the ideas got too intermixed and intermingled to cite directly in the text:

- Post-Artifact Books and Publishing, by Craig Mod

- Book: A Futurist’s Manifesto: A Collection of Essays from the Bleeding Edge of Publishing

Follow us for the latest updates and insights around productivity and Building a Second Brain on Twitter, Facebook, Instagram, LinkedIn, and YouTube. And if you're ready to start building your Second Brain, get the book and learn the proven method to organize your digital life and unlock your creative potential.