Over the past few weeks, we completed our first rigorous cost-cutting exercise in the 10 years Forte Labs has been in business.

Cost-cutting is a strange subject to talk about as a creator-led business. We’re not supposed to worry about those pesky annoyances called “expenses” or “profitability.” We’re on the Internet, and the Internet is a wide-open frontier of endless possibility, right?

Right?!

But as 2022 came to a close, we began to see signs of a weakening online education sector after several years of white-hot growth. Whether it was expectations of a looming recession, punishing inflation, or a post-pandemic preference for in-person experiences versus online events, I don’t know.

What I do know is that people are more hesitant to take out their wallets and spend their money on online self-development programs than at any time since before the COVID pandemic. I decided to learn how other companies typically approached cost-cutting and to review our expenses in the new year.

The results?

We saved $27,764 in recurring annual expenses, equaling about 3% of our non-labor costs. More importantly, we questioned where our money is going and what we really need to serve our customers. That led to a more realistic understanding of which software platforms and services are essential for us.

Finally, we seem to have cultivated a mindset of frugality in our company culture that’s already reaping rewards as we’re faced with countless special offers and “must-have” purchases heading into the new year.

Read on to find out how we did it, and get a checklist you can use to perform a similar feat in your own company, organization, or life.

The mindset of profit-maximization

The single most important thing I needed to do to cut costs effectively was to change my mindset toward money.

The last decade has been one of the strongest bull markets for online businesses ever, capped by two years of completely unprecedented, explosive growth. A decade of plenty instilled in me an attitude that it was so much easier and more fruitful to spend my time growing revenue rather than pinching pennies. It felt like we should spend money as fast as possible in order to make money even faster.

A mindset of abundance makes sense when the environment is one of abundance. But an environment of scarcity demands an attitude resilient to scarcity. In order to make a cultural shift within our company, I first needed to make that shift psychologically myself.

I asked Twitter how I could learn to become frugal, and picked up one of the recommended books, Double Your Profits in 6 Months Or Less (affiliate link) by Bob Fifer. The title sounded like a late-night infomercial, and the cover looked like it was from the 90s, which I soon discovered was accurate: the book was first published in 1993.

In Internet terms, an ancient relic.

As I opened its pages, the author’s writing reflected an old-school attitude to business that I barely recognized. He sounded like a survivor of the Great Depression, scrounging for every nickel and treating every cost as a personal offense.

But as I continued reading, Fifer slowly introduced me to a powerful framework for thinking about costs during uncertain economic times. Here are a few of the most important takeaways that I decided needed to become part of our culture:

- Our driving goal as a company is to be THE BEST in our field, which means we must maximize profit, which is the “permission to keep going.” All other goals or objectives don’t matter if we’re not profitable.

- To maximize profit, we need to consistently ask “What is the customer willing to pay for?” and eliminate everything else.

- All costs can be divided into 1) Strategic costs (essential for generating revenue) and 2) Non-strategic costs (not essential for revenue). Our goal is to spend more on the former than any of our competitors and cut the latter to the bone.

- Keeping resources (human and monetary) purposefully scarce forces us to soul-search about which tasks and projects are truly value-producing.

- Always make the spending of money a difficult process so that people must jump through several hoops to prove its worthiness.

- Every cost should be treated as a necessary evil at best, and we should look for any possible way to eliminate it.

- When considering eliminating an expense, ask yourself, “If I eliminated this cost, would I immediately lose revenue or profits? How and where?”

- If in doubt, default to cutting a cost, and if a consequence emerges, you can always add it back (whereas leaving it in place means that money is gone forever).

- The hardest part of all of your cost-cutting initiatives will be the resistance to change you will encounter. People learn to treat every service as essential even when it’s not.

As hard as this may be to believe, I had never really thought that the #1 job as a CEO is to maximize profit. With revenue doubling every year, and gross margins consistently above 60%, profitability seemed to more or less take care of itself. All that was left to do for us was to figure out how to spend it.

Which is why this quote rang so powerfully inside my head: “Full empowerment of an organization when you have not focused on profits is an abdication of your most basic responsibility as a leader.”

I could see with sudden, newfound clarity that nothing else we achieved – big product launches, huge audience growth, a bestselling book, prestigious media attention, or even an empowered team – meant anything if we weren’t profitable.

I was encountering a set of timeless, conservative business principles for the first time, and it all seemed new again.

Cost-cutting as a ritual

With my new mindset in place, I wanted to spring immediately into action and begin eliminating costs right, left, and center.

But I knew that cost-cutting wasn’t a one-time event – it was a repeatable ritual that we would need to do again and again indefinitely. I resolved to move slowly and purposefully instead, documenting every step we took, every question we asked, and every unnecessary expense we identified for future reference.

Here were the 9 main elements of the cost-cutting process I put in place:

- Formed a Budget Committee made up of me, our Director of Operations, and Business Operations Manager, with a standing monthly meeting

- Set aside time for a year-end review of every single transaction over the last quarter, in order to identify candidates for cost reduction

- Scheduled monthly reviews of every transaction going forward (to question whether it’s necessary, can be reduced, and to categorize it correctly)

- Reached out to our main suppliers, contractors, and service providers to proactively negotiate price reductions (or extend payables or other terms)

- Instituted a new policy that all new costs must be approved by me personally

- Reviewed employee benefits to decide which ones people truly value, cutting the rest

- Wrote an internal memo to all staff explaining what we were doing and why it was important to our goals as a company

- Asked every person on our team to suggest ideas for expenses we could reduce or eliminate

- Broke down our financial statements into 4 departments – Product, Operations, Marketing/Content, and YouTube – with each Director responsible for controlling their own spending

I also shared with the team a set of questions we would be using to question how we had spent money in the past, partly drawn from the book and partly from my own experience:

- What is the customer willing to pay for? What are they not?

- Which difficult, uncertain expenses are we avoiding to cut in favor of easy, clear reductions?

- How can we make the process of spending money more difficult?

- Where can I personally set an example of how much we value each dollar?

- How can we make our company more of a meritocracy, rewarding those who contribute directly to the bottom line?

- How can we create a profit-maximized customer, instead of just a happy one?

- How can we remove benefits that employees don’t value, in favor of the ones they do?

- How can we create an attractive offering for each major category of customer at a price they are willing to pay?

Examining our credit card statements with a critical eye, I decided we needed to put as much thought into keeping money as we put into earning it in the first place.

How we reviewed every transaction

Our newly formed Budget Committee kicked things off by reviewing each and every transaction in the last quarter of 2022.

Our goal was not only to come up with a list of specific expenses to eliminate but to create a baseline that future quarters could be compared to. We also took the time to make sure expenses were assigned to the correct department, so that future decisions about where to invest would be more accurate.

The prospect of reviewing each and every transaction for a quarter – over 700 in total – might seem daunting, but we developed a succinct set of questions to accelerate progress. Here were the questions we asked for each item:

- “Is this expense truly necessary?”: If not, cancel it (and ask for a refund for any unused periods)

- If it is necessary, then ask: “How can this cost be reduced?”

- Can it be paused when not needed?

- Can it be downgraded to a cheaper plan or lower level of service?

- Can it be switched from monthly to annual billing (to save money) or from annual to monthly (if it’s only needed occasionally)?

- Can we negotiate a better price?

- If it still remains, then finish by asking: “Which department should this be assigned to?”

- Take notes on any follow-up actions needed (to find out more details about a service from the person who uses it, and share corrections with our bookkeepers so they can accurately categorize transactions in the future)

As we walked through these questions, we were surprised by how many opportunities there were for cost reduction. We thought we ran a lean operation, but even for services that we couldn’t eliminate completely, there was often a more basic plan or smaller number of users that served our needs just fine.

Renegotiating rates with our suppliers and contractors

Our next task was to see how we could reduce how much we spent on suppliers, service providers, and contractors, which made up a significant chunk of our spending.

I found this can take many forms, and doesn’t have to be adversarial. People understood that we need to look out for our profitability and were often willing to work with us to keep us as a customer in uncertain economic times that they’re probably feeling themselves.

This part is ongoing and might include switching contractors from retainer to hourly billing (or vice-versa), asking them to add more value in lieu of reducing their rates, asking them to cover costs that are essential to their work (as is appropriate for contractors), requesting more favorable terms such as longer payable periods, seeking bulk discounts for suppliers we buy a lot from and other requests.

SaaS services were much easier to reduce since they often have extremely high margins of 70-90% and thus are willing to keep you at almost any cost. We found that in some cases simply asking for a discount was effective.

The key to all these conversations was for the negotiation to come directly from me, the CEO, since the staffperson who works most closely with a contractor is often on too friendly of terms to make such requests.

The results of our cost-cutting exercise

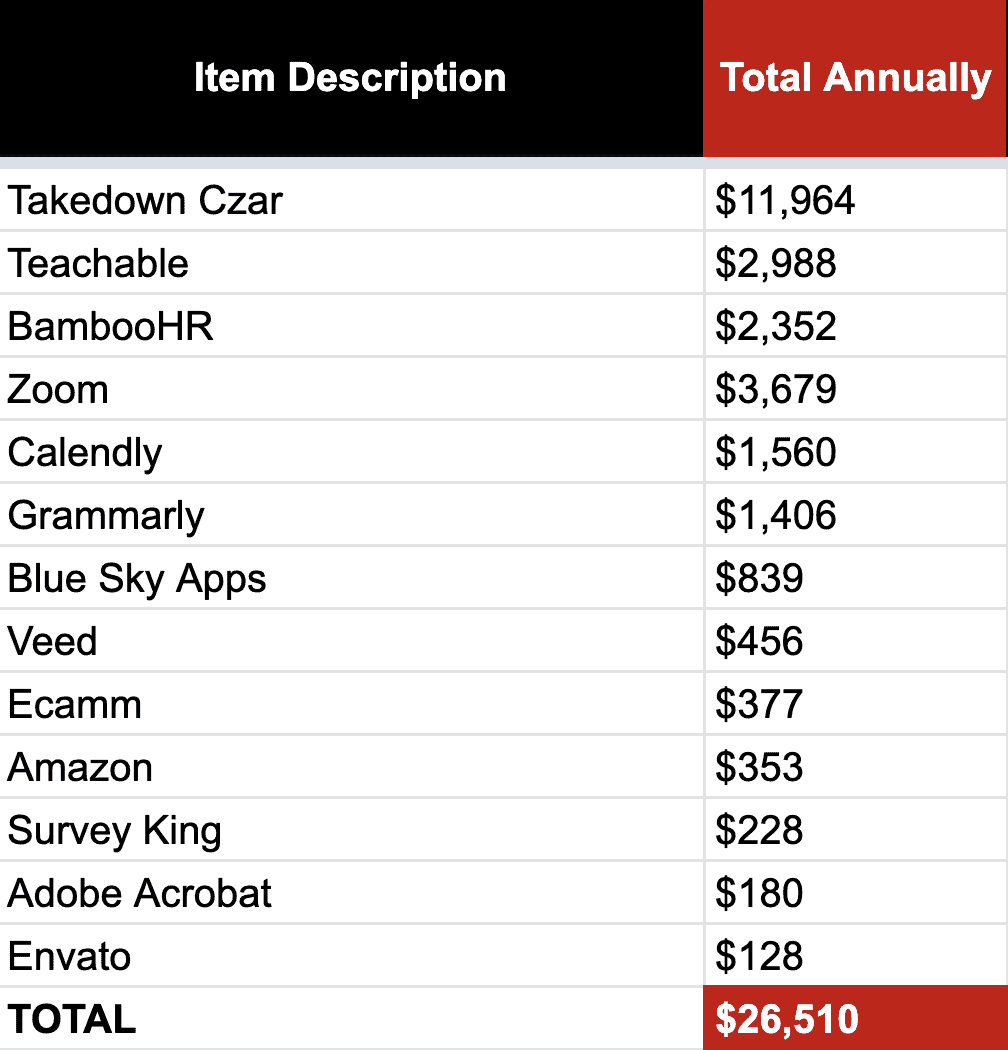

At this point you’re probably wondering what we cut exactly. Here’s the full list, including full cancellations and partial reductions on an annual basis:

In addition to $26,510 in planned spending, we received $1,254 in refunds from some of the services above for unused periods. The grand total of $27,764 represents about 3% of our annual non-labor costs, and 1.3% of our total costs, a sizable chunk of recurring spending that meaningfully improves our profitability for the coming year and beyond.

More important than the numbers, however, is the psychological effect of working through this process as a team. To my surprise, I found it required tremendous creativity and imagination. It’s forcing us to learn how to hack together jerry-rigged solutions to problems instead of just buying something off the shelf. As a result, we’re discovering how adaptable and resilient we are, and how possible it is to do more with less.

If constraints are necessary for innovation, purposefully creating financial constraints around our spending has channeled our problem-solving ability and helped us prioritize what’s truly necessary from what isn’t. And through it all, we are finding new ways to rely on each other and hold each other accountable to protect the only number that proves we are creating value: profit.

If you want to know which software tools, apps, and services we continue using, click here. These are the ones we’ve found essential for running and growing our business.

- POSTED IN: Books, Case studies, Entrepreneurship, Strategy