An Integrated Total Life Management System

By Tiago Forte of Forte Labs

To learn more, check out our online bootcamp on Personal Knowledge Management, Building a Second Brain.

One of the key insights of Getting Things Done, the book on personal productivity by David Allen that spawned the worldwide movement known as GTD, was that knowledge workers could instantly and massively reduce information overload just by clearly separating actionable from non-actionable information, and then giving priority to the former.

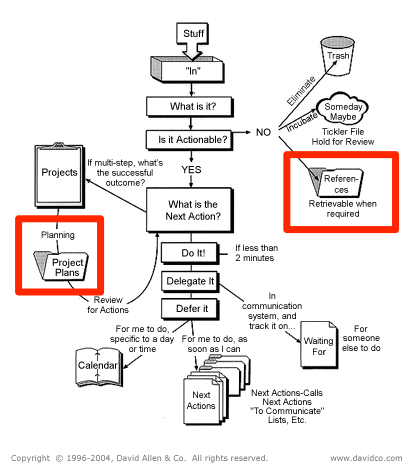

This division of the waters is clear when you look at the original GTD workflow diagram:

Non-actionable information gets diverted to the right side as “general reference,” and to the left side as “project plans.” Actionable information — things you must do, delegate, or defer — flows down the central spine, and is clearly the priority.

But the nature of work is rapidly changing. Our organizations are characterized like never before by job-hopping, mergers and acquisitions, layoffs and reorganizations, outsourcing and automation, harsh competitive environments and even harsher startup ecosystems. Meanwhile, the number of freelancers, online businesses, and independent contractors is exploding.

For our purposes, all these trends have an important impact: the average employee tenure is plummeting (to just 2.3 years for employees ages 20–34, as of a few years ago). I believe this means that the relative importance of “non-actionable information” is rising. We can now expect to spend only a few months to a few years with one organization, which means our ability to capture, organize, and retrieve our ideas, and transfer them effectively from project to project and company to company, becomes more important than ever.

In 2015, David Allen published an updated edition (affiliate link) of Getting Things Done that sheds light on this trend. Littered throughout the book are tantalizing hints of what Allen sees as the future of GTD, and of productivity: what he calls an “integrated total life-management system.”

Again and again, he hammers on the critical importance of “a good general-reference file” as “one of the biggest bottlenecks in implementing an efficient personal management system.” He emphasizes that, “For most of the executives I have coached, it represents one of the biggest opportunities for improvement.”

He goes on to explain that, although these materials are “seldom associated with urgency, nor are they strategic…”, if left unmanaged “your mental and physical workspaces become cluttered with non-actionable but potentially relevant and useful stuff.” This lack of effective downstream systems, he claims, eventually produces a “debilitating psychological noise” that makes any kind of creative thinking impossible. We’ve all been there.

“If you don’t have a good system for storing bad ideas, you probably don’t have one for filing good ones, either.”

— David Allen

In an economy driven by creativity and innovation, not having a personal knowledge management (PKM) system means you’re not fully leveraging what you learn. You’re not collecting your ideas and making serendipitous connections between them. You’re not offloading your best thinking onto reliable tools, freeing your conscious mind to focus on creating novel value. You are in danger of becoming what Ben Horowitz warns against in his book The Hard Thing About Hard Things: a “content-free” employee.

Allen goes on to lay out many of the qualities such a reference system should have:

- “You will resist the whole process of capturing information if your reference systems are not fast, functional, and fun.”

- “The great thing about external brainstorming is that in addition to capturing your original ideas, it can…continually reflect them back to you.”

- “There must be zero resistance to using the systems we have.”

- “…the ease of capturing and storing has generated a write-only syndrome: all they’re doing is capturing information — not actually accessing and using it intelligently.”

- “We need to have a way to overview our mass of collected information with some form of effective categorization.”

But this new frontier presents a challenge: the world of non-actionable information — long-term, asynchronous, open-ended research on creative projects — is very murky, with no “clean edges” or “next physical actions” to speak of. It is not at all clear at the outset what a piece of information means, how it will be used, how important it is, or even what category it falls into. And the more creative and the more interests one has, the worse this problem gets.

Creating a system of personal knowledge management is a design problem. And like all design problems, it must balance and trade off multiple priorities against each other: the balance between order and serendipity; between being goal-directed and allowing our thinking to lead us to unexpected places; between supporting our existing viewpoints and challenging us with new ones. Such a system needs to help us cultivate what Roger Martin called an opposable mind — the ability to hold two opposing ideas in our mind at the same time — without taxing our ability to actually get things done.

Allen notes that “Software is now available that allows capturing and categorizing this kind of information (and synchronizing it with multiple devices), but it does require some thought about how to structure it, as well as some directed behavior to flow this kind of stuff into appropriate places instead of complicating and confusing your digital environment.”

If you’re interested in developing such a system, my online bootcamp on personal knowledge management teaches you how to select and set up that software, create that structure, and perform those directed behaviors. Version 4.0 starts November 6: Building a Second Brain: Capture, Organize, and Share Your Ideas Using Digital Notes.

In the closing pages of the updated book, Allen describes what it is like living in such a state of presence and awareness, freed from remembering and therefore free to think:

“You’re not at a loss about what to do with anything — a business card you collected at a lunch meeting, a harebrained idea you woke up with this morning about a project you might want to launch, an unexpected private invitation to a major gala event, or your blood panel report from your last medical checkup. You can create the right placeholder for any type of potentially meaningful data.”

I can attest that this state of mind is possible, and in a weird way, it’s easier. It requires understanding our human nature, instead of fighting it. It requires looking for ways to do less, not assuming doing more is always better. It requires self-awareness and self-acceptance, seeing our limiting beliefs as opportunities for explosive growth, if we have the courage to face them.

But all this starts with a practical system to get things going — before you make it better, you have to make it work. Or as Allen puts it, “…a system for getting things out of your head and into objective, reviewable formats — building an extended mind.”

Join us on November 6th, or check out the course page with testimonials, course components, the schedule, the full curriculum, frequently asked questions, a sample video, and further reading to put this new approach into context.

Follow us for the latest updates and insights around productivity and Building a Second Brain on Twitter, Facebook, Instagram, LinkedIn, and YouTube. And if you're ready to start building your Second Brain, get the book and learn the proven method to organize your digital life and unlock your creative potential.

- POSTED IN: Books, Building a Second Brain, Note-taking, Organizing, Productivity, Workflow