This post also available in Dutch

Note-taking is an ancient activity, practiced across cultures, languages, and writing systems for millennia.

It is distinct from simply writing things down. For our purposes, note-taking is:

- Personal, informal, quick and dirty: notes are optimized not for public consumption, but for your own personal use, like a leather notebook you keep in your backpack

- Open-ended and never finished: “taking notes” is a continuous and generative process, in which you can noodle on ideas without an explicit purpose in mind

- Low friction: notes impose low standards for quality and polish, which means they are easy to add to, subtract from, and edit, and can be messy, incomplete, or totally random

- Multimedia: just like a paper notebook might contain drawings and sketches, quotes and ideas, and even a pasted photo or post-it note, notes naturally combine diverse types of media in one place

What further distinguishes creative note-taking from the general purpose kind is that such notes are not meant for a one-time project. They are meant for a lifetime of continuous, open-ended learning and creative output.

This series will look at notable examples of this kind of creative note-taking throughout history, to extract useful techniques and timeless principles for our own personal knowledge management in the 21st century.

Our first two are German sociologist Niklas Luhmann and Renaissance scientist and artist Leonardo da Vinci.

Niklas Luhmann’s Zettelkasten

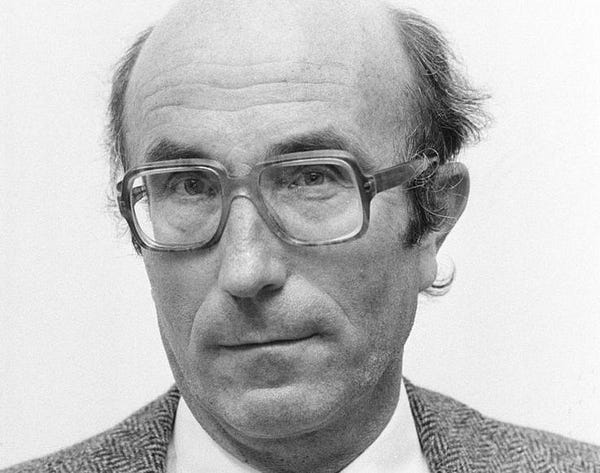

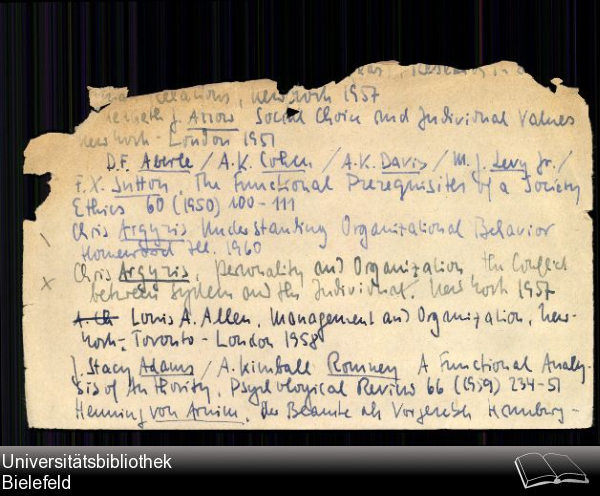

One of the most comprehensive and influential historical sources of note-taking was the “Zettelkasten” developed by German sociologist Niklas Luhmann (1927–1998). His approach is described in this blog post.

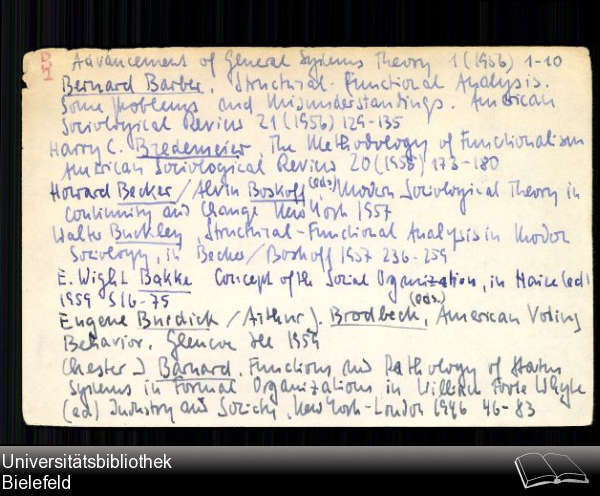

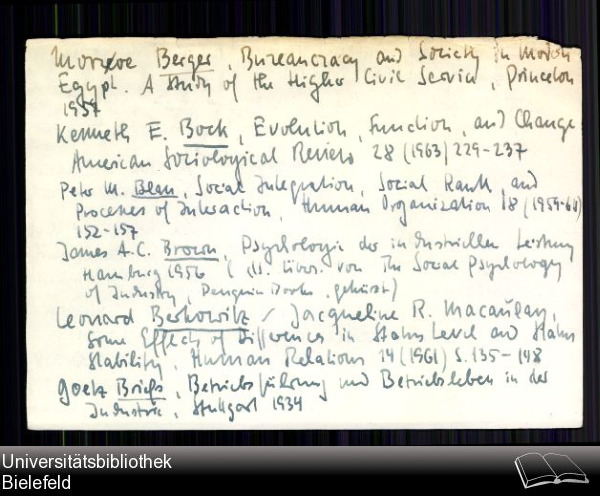

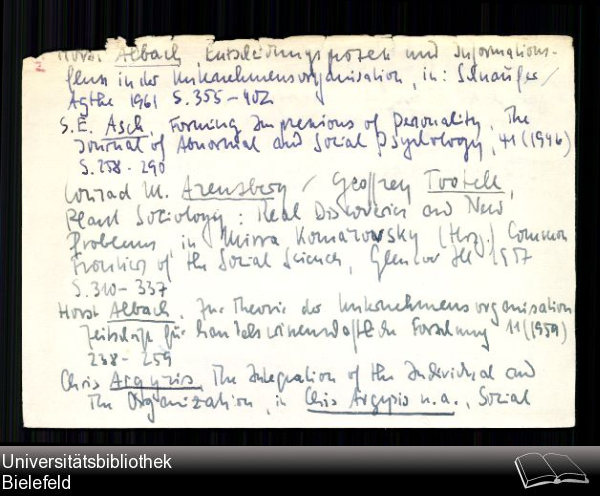

Luhmann rejected alphabetical categorization of his notes, along with pre-determined categories like the Dewey Decimal System. He intended his notes not just for a single project or book, but for a lifetime of reading and researching. He invented a research database made up of index cards (Zettel) that was “thematically unlimited” — that could be infinitely extended in any direction.

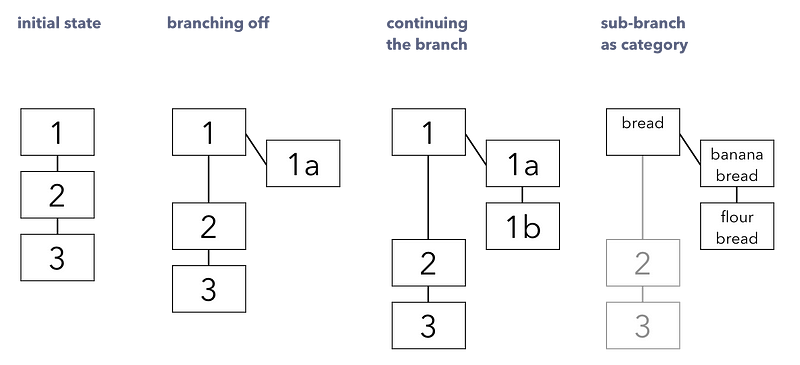

Each index card received a sequential number, starting at 1. When a new source was added to that topic, or he found something to supplement it, he would add new index cards with letters as suffixes (1a, 1b, 1c, etc.). These branching connections were marked in red, as close as possible to the point where the branch began. Any of these branches could also have their own branches. The card for fellow German sociologist Jürgen Habermas, for example, was labeled 21/3d26g53.

Not only did this create a system that could be extended infinitely in any direction, it also gave each index card a permanent ID number (Folgezettel). This number could be referenced from any other card, because it would never change. The branches created “strands” of thought that one could enter into at any point, following it downstream to be elaborated upon, or upstream to its source.

It also led to a meaningful topography within the system: topics that had been extensively explored had long reference numbers, making their length informative on its own. There is no hierarchy in the Zettelkasten, no privileged place, which means it can grow internally without any preconceived scheme. By creating notes as a decentralized network instead of a hierarchical tree, Luhmann anticipated hypertext and URLs.

Luhmann described his system as his secondary memory (Zweitgedächtnis), alter ego, or reading memory (Lesegedächtnis). He spoke of it as an equal thinking partner in his work. He reported that it had the capacity to continuously surprise him with ideas he’d forgotten he had. Because of this, he claimed that there was actual communication going on between himself and his Zettelkasten.

Lessons and takeaways

I draw 4 lessons from Luhmann’s work:

Long time horizons change the game

Luhmann was a visionary in seeing that a notecard system could be much more than a one-time project support tool. It could last for decades, becoming as integral to our thinking and work as the memories in our head. Paradoxically, creating such a lifelong system becomes even more important as the media we consume changes faster and faster.

Categorization can itself be creative

Luhmann refused to be content with existing categorization systems. Perhaps his greatest idea was not anything contained on an index card, but how those index cards were linked together — in a decentralized network using permanent ID numbers. It’s a good reminder that we don’t have to accept anything as given when it comes to organizing information.

Good notes do not depend on technology

It has been a constant temptation over the centuries to obsess over note-taking tools. This was as true in the era of pitched battles over the correct size of index cards, as modern debates about Vim vs. Emacs. Luhmann didn’t get caught up in these controversies. He made a “good enough” system and then focused his energies on collecting ideas and producing content (70 books and 400 scholarly articles, for example).

Our second brain can think and communicate, not just remember

Luhmann entered almost metaphysical territory with his comments later in life on what his Zettelkasten was capable of. He claimed that it was an equal thought partner, not just a tool. He argued that it could think and communicate, which is a powerful call to raise our expectations about what digital tools can do for us.

Here’s a post on the Zettelkasten forum about how my “second brain” techniques relate to Luhmann’s methods.

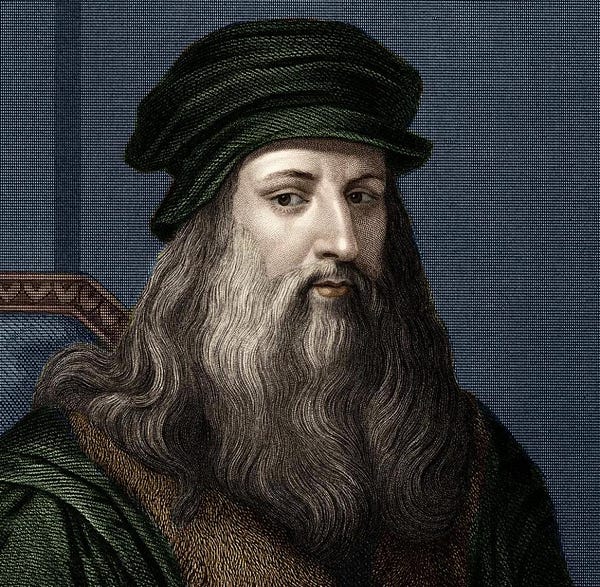

Leonardo da Vinci’s notebooks

This New Yorker article tells us about Da Vinci’s notebooks, as told in Walter Isaacson’s new biography Leonardo da Vinci.

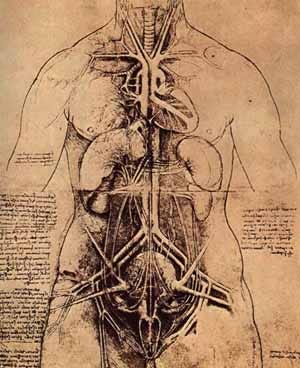

Over 7,000 pages of Leonardo’s notes survive until today. Some were from private notebooks he carried around for quick sketches and observations. Others were for long-term studies in geology, botany, human anatomy, music, military engineering, astronomy, and many other areas.

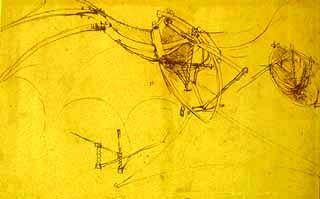

Leonardo’s notes were not meant primarily for self-exploration, like a journal or diary. They were turned on the world, a continuous log of his explorations and experiments. There’s no clear line between the fanciful and the practical: on one page he studied the flight mechanics of birds, on another designed a flying machine, and on the next described his efforts building it. It’s not known whether he actually tried to fly it, but his later designs for a parachute system give us some indication of how it might have gone.

Da Vinci’s notebooks were an expression of his combinatorial style of creativity, dashing across the boundaries between fields. It is impossible to distinguish, in his notes, where science ended and art began, or where his observations ended, and his imagination began. Behind the Mona Lisa’s famously enigmatic smile, we find pages and pages of studies of lip muscles, which Leonardo drew both with and without skin. On another page examining the flight patterns of birds, he absentmindedly recalled a childhood memory, a dream in which a bird flew down from the sky and struck him in the mouth.

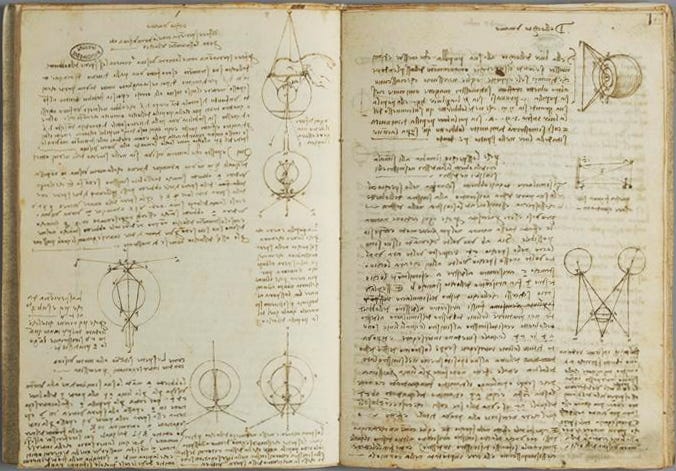

His notebooks follow the “personal, informal, quick and dirty” criteria very well: they were minimally organized, with quick, messy lettering clearly intended only for his own use. He used a personalized shorthand, and in many places his pen seems to have barely touched the page as he raced to keep up with his thoughts.

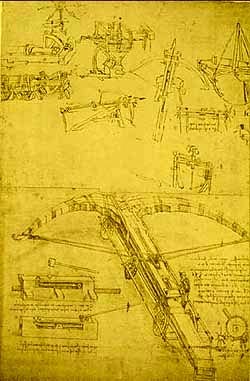

There is repeated evidence throughout his life of how highly Leonardo thought of his notes. They provide a backstory to many of his greatest works, even the ones that were never started. The only evidence we have of his unfulfilled commission to paint a wall of Florence’s Great Hall, for example, is his preparatory drawings, which suggest it would have been a masterpiece. His notes served as a work-in-process record of his many projects, which later turned into precious historical records. For example, the massive bronze sculpture of a horse commissioned by Ludovico Sforza, the Duke of Milan, which he never finished. It was later sent off to be melted down and turned into cannons, and we only know about it because of his preparatory sketches.

To speculate a bit, it seems likely that Leonardo’s notebooks both facilitated his extremely diverse projects and lifestyles, and also allowed him to learn and extract value from everything he worked on, even if it wasn’t finished or soon faded. He bounced around from state to state, working on whatever allowed him to get by and earn enough money to live. In his 30 preparatory drawings for a giant crossbow, for example, we see a mind interested not just in killing efficiency, but one obsessed with mechanical principles that would later show up in dozens of other designs.

In his 50s, fearing the end of his life was near, Leonardo turned away from painting to complete his studies and organize his notes. In our last record of him, in a visit from the Cardinal of Aragon in France, he showed off those notebooks, calling them an “infinity of volumes.” It makes me wonder whether, hundreds of years from now, Da Vinci will be remembered just as much for his creative process — which is timeless and universal — as for his paintings, which will inevitably fade.

Lessons and takeaways

I draw 3 lessons from Da Vinci’s notebooks:

There are hidden gems in our notes

Even though he was celebrated as a genius during his lifetime, it took centuries for us to fully appreciate Leonardo’s brilliance. His engineering designs were centuries ahead of their time, and might have worked with modern materials and some small tweaks. He seems to have used and described the scientific method long before it was invented, writing in one of his notebooks:

“First I shall make some experiments before I proceed further, because my intention is to consult experience first and then by means of reasoning show why such experiment is bound to work in such a way. And this is the rule by which those who analyze natural effects must proceed; and although nature begins with the cause and ends with the experience, we must follow the opposite course, namely (as I said before), begin with the experience and by means of it investigate the cause.”

This is a reminder that we ourselves don’t know which ideas in our notes will end up being the most important, impactful, or innovative. To discover that, we need to capture everything, test it early and often, and make tangible artifacts to share with the world.

Notes are a means to an end

It is very tempting to make notes into ritualistic totems. To obsess over the grain of the paper, the thickness of the pencil, or the default spacing and font. All of this takes away from the act of creation. Leonardo’s notes were so chaotic and messy they border on being unintelligible, even for him. He understood that it was the final product — The Last Supper, or the Mona Lisa — that would truly make a mark. All the notes created along the way paled in comparison.

Notes deserve respect

Despite the above, notes are also worthy of our respect. It is only when we start treating our ideas as worth capturing and reviewing, that we start to have more good ideas in the first place. Leonardo in his later years spoke of his notebooks with something close to reverence. Our identity depends on our memory — expanding our ability to remember things also potentially expands our sense of who we are.

Check out Walter Isaacson’s new biography of Leonardo da Vinci (Amazon Affiliate Link), which uses his notebooks as a starting point, and from which these examples are drawn.

Principles and techniques

Principles are higher than techniques. Principles produce techniques in an instant. — Ido Portal

What we are looking for in these historical examples are principles and techniques. Principles are timeless and universal, but often difficult to see clearly. Techniques are temporary and context-dependent, but concrete, giving us clues about the principles they operate on.

Which principles or techniques resonate most with you from these two examples?

Follow us for the latest updates and insights around productivity and Building a Second Brain on X, Facebook, Instagram, LinkedIn, and YouTube. And if you're ready to start building your Second Brain, get the book and learn the proven method to organize your digital life and unlock your creative potential.

- Posted in Building a Second Brain, Note-taking, Organizing

- On

- BY Tiago Forte