Writing down your open questions is an act of “externalization” – you are taking passing curiosities and interests from your mind and externalizing them into the outside world.

That is a first step to making those questions active generators of possibility in your life, but certainly not the last. Once they exist in written form, such as in your notes, you now have a place to begin collecting potential answers to those questions without having to memorize them.

A question is like a radio signal broadcast out into space. It’s only natural that you’ll want to record any replies that come back.

Let’s revisit Richard Feynman’s story and see how he did exactly that.

Working from first principles

Richard Feynman was famous for always working “from first principles.”

He always started with the most basic facts, asked the most seemingly obvious questions, and let no assumption pass by untested. Rather than blindly accepting the wisdom of outside authorities, he drilled down to the most fundamental principles he could find and built up his own understanding from there.

This often led people to underestimate him, thinking he was slow to understand the problem at hand. As he recounted in his book Surely You’re Joking, Mr. Feynman! (affiliate link) (emphasis mine):

“Some people think in the beginning that I’m kind of slow and I don’t understand the problem, because I ask a lot of these “dumb” questions: “Is a cathode plus or minus? Is an an-ion this way, or that way?”

But later, when the guy’s in the middle of a bunch of equations, he’ll say something and I’ll say, “Wait a minute! There’s an error! That can’t be right!” The guy looks at his equations, and sure enough, after a while, he finds the mistake and wonders, “How the hell did this guy, who hardly understood at the beginning, find that mistake in the mess of all these equations?”

He was willing to appear “dumb” and ask questions that everyone else was afraid of asking, in order to arrive at answers no one else was capable of finding.

For Feynman, knowledge did not just describe. It acted and accomplished. It was a pragmatic tool for predicting and shaping reality. For that reason, he wasn’t content to learn the names of things or abstract explanations of how they worked. He believed that it was only through empirical trial and error that the truth could be distilled from mere conjecture.

Extending the mind

In her excellent book The Extended Mind (affiliate link), author Annie Murphy Paul introduces an exciting new field called “extended cognition.”

Based on extensive academic research, she makes a compelling case that human thinking doesn’t end at the boundaries of our skulls. Instead, our brains are just one part of a greater system of cognition that transcends our purely mental abilities.

Paul argues that there are three main ways humans extend their thinking capabilities in this way:

- Thinking with the body

- Thinking with the environment

- Thinking with other people

Decades before extended cognition was even recognized as a field of study, Feynman used all three of these mechanisms to amplify his intellectual and creative powers. Even such a formidable mind as his relied heavily on outside sources of intelligence to achieve his intellectual heights.

Thinking with the body

Feynman was known for his physicality, perhaps surprising for a theoretical physicist.

Feynman’s biographer James Gleick noted that “Those who watched Feynman in moments of intense concentration came away with a strong, even disturbing sense of the physicality of the process, as though his brain did not stop with the gray matter but extended through every muscle in his body.”

He would often be seen tapping rhythmically with his fingers on tabletops or other objects, gesticulating wildly as he talked, or using props to communicate ideas.

Feynman often described how he used visualization to put himself in nature: in an imagined beam of light, in a relativistic electron. Once he could see things from an electron’s point of view, new possibilities suddenly opened up to him.

The mathematical symbols he used every day had become entangled with his physical sensations of motion, pressure, and acceleration to the point that he “saw” physics in living color and “felt” the motions of particles as bodily sensations.

Gleick recounts a remark by a colleague of Feynman’s flabbergasted by his ability to make unexplainable intuitive leaps:

He suspected that when Feynman wanted to know what an electron would do under given circumstances he merely asked himself, “If I were an electron, what would I do?”

The colleague was joking, but his explanation was more accurate than he realized.

Thinking with the environment

Feynman’s commitment to testing ideas through direct interaction with the physical world extended to the tools he used to do so, especially his notes.

Gleick tells the story of how Feynman prepared for his oral qualifying examination to graduate from MIT. In typical fashion, he refused to read the standard papers of his field – he didn’t want his perspective to be colored by what other physicists thought was possible (or impossible).

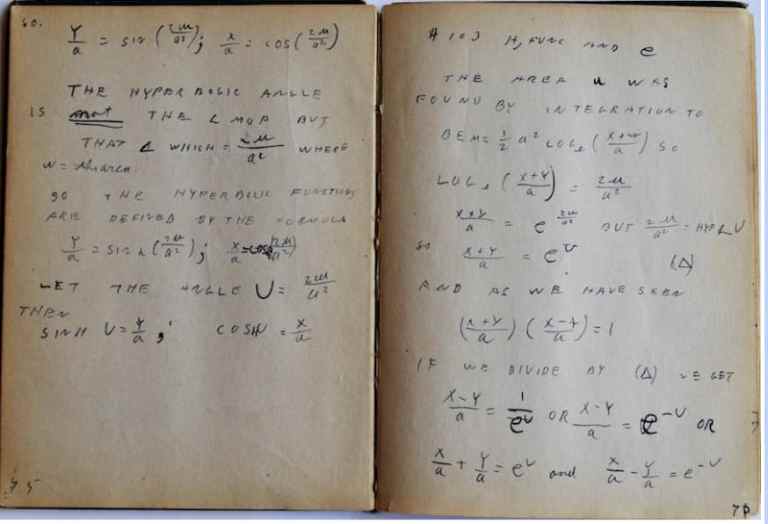

Instead, he opened up a fresh notebook, turned to the first page, and wrote: Notebook of Things I Don’t Know About. For the first time (but not the last), he began to reorganize his knowledge of physics on the page. He worked for weeks disassembling each branch of physics he thought he understood, before putting it all back together and looking for raw edges and inconsistencies.

He took apart ideas on the page like a mechanic takes apart an engine – refusing to trust that anything fit without trying it out himself. His notebooks were like free-form canvases one might find in an artist’s studio, containing (according to his biography) “not just the principles of these subjects but also extensive tables of trigonometric functions and integrals—not copied but calculated, often by original techniques that he devised for the purpose.”

Much later in life, Feynman was interviewed at his home by the historian Charles Weiner, who was considering writing an official biography of the man. They were discussing Feynman’s attitude toward his notes, and Weiner casually observed that they represented “a record of the day-to-day work.”

Feynman sharply disagreed (emphasis mine):

“I actually did the work on the paper,” Feynman countered.

“Well,” Weiner said, “the work was done in your head, but the record of it is still here.”

“No, it’s not a record, not really. It’s working. You have to work on paper, and this is the paper. Okay?”

This distinction may seem small but was a crucial one for him: Feynman didn’t do the thinking in his head, only to record it afterward in his notebooks. The interaction between his mind and his notes constituted his thinking. Together they formed an integrated system of cognition criss-crossing the boundaries between flesh and paper.

Thinking with others

Feynman was known as a singular genius, but that doesn’t mean he worked in isolation. He relied heavily on connection and collaboration with other leading minds of his era, both within and outside of physics.

His Nobel Prize in 1965 was shared with two other collaborators, Julian Schwinger and Sin-Itiro Tomonaga, each of whom contributed critical insights to the emerging understanding of quantum physics. He learned from mentors like Hans Bethe, a German-American theoretical physicist who was a major influence in teaching him how to understand physics from first principles.

Even beyond his professional life, his family and friends shaped him into a far more well-rounded, empathetic person than he was naturally inclined to be. Feynman recalled fondly how his mother taught him that “the highest forms of understanding we can achieve are laughter and human compassion.” His high school sweetheart and first wife Arline taught him to not take himself too seriously by teasing him about his pride and ego.

Feynman’s numerous and deep collaborations point to one of the most profound side effects of seeing the world through open questions: they will inevitably bring into your life people who share the same questions.

The purpose of generating your list isn’t just to clarify your own pursuits. Once you have this list in hand, it can serve as an invitation to the people you want to attract into your life – whether as friends, romantic partners, collaborators, colleagues, supporters, or investors.

When you are clear on the questions you are immersing yourself in, it makes it much easier for others to identify what kind of person you are and what you are trying to create in the world. When others can see what you’re trying to accomplish, it becomes far easier for them to help you do so.

A leader is not someone who relentlessly advances their own opinion through the opposition of others. A leader is someone who insistently asks a big question, again and again, creating a space of possibility into which others can pour their own contributions.

A close relative of Feynman’s favorite problems is a discipline known as Appreciative Inquiry. It involves asking questions not as a form of criticism, but (as the Wikipedia article above puts it) “to stimulate new ideas, stories and images that generate new possibilities for action.”

The article goes on: “Questions are never neutral, they are fateful, and social systems move in the direction of the questions they most persistently and passionately discuss.” And on an even grander scale: “Human systems are forever projecting ahead of themselves a horizon of expectation that brings the future powerfully into the present as a mobilizing agent.”

In other words, our future unfolds as a result of the questions we ask ourselves in the present. As long as those questions are externalized and made concrete in the world beyond our heads.

In Part 4, I will present a case study of how I used an evolving set of open questions to guide my career through years of uncertainty, ultimately leading to finding a calling that uniquely aligned with my deepest curiosities and passions.

A big thank you to Chris Winterhoff, Diana, Eric Colby, Julia Saxena, and Marla Maestre Meyer for their feedback and suggestions on this piece.

Follow us for the latest updates and insights around productivity and Building a Second Brain on Twitter, Facebook, Instagram, LinkedIn, and YouTube. And if you’re ready to start building your Second Brain, get the book and learn the proven method to organize your digital life and unlock your creative potential.

- POSTED IN: Creativity, Goals, Personal growth, Productivity