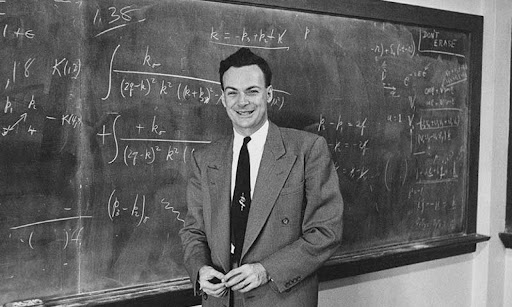

Richard Phillips Feynman was one of the most important scientists of the 20th century.

Born on the outskirts of New York City in 1918, his work in theoretical physics radically reshaped our understanding of the universe we live in at the most fundamental subatomic levels.

When it was all said and done, his biography would simply and fittingly be titled Genius (affiliate link). It is the astonishing story of a mind grappling with the deepest questions we can ask about reality, and against all odds, arriving at useful answers.

But Feynman’s brilliance was not solely due to his natural cognitive abilities. He relied on a method: a simple technique for seeing the world through the lens of open-ended questions, which he called his “favorite problems.”

You can create a list of your own favorite problems – a concrete set of questions you rely on both to filter the information you consume and to connect the dots between challenges and potential solutions.

They allow you to:

- Dedicate your time and attention to ideas that truly spark your curiosity

- See how a piece of information might be useful and why it’s worth keeping

- See insightful patterns across multiple subjects that seem unrelated, but might share a common thread

- Focus the impact of your work on problems where you can make a real difference

- Prime your subconscious to notice helpful solutions to your biggest challenges in the world around you

- Attract like-minded people who have the same interests and goals as you

A modern Renaissance Man

Feynman helped pioneer the emerging field of quantum physics, which dramatically changed our understanding of matter and energy in the 20th century.

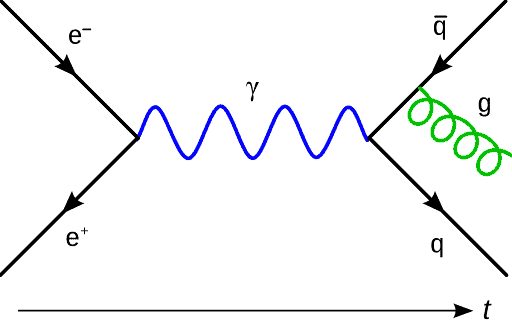

In 1965, he won the Nobel Prize for his invention of “Feynman Diagrams,” a notation system that allowed physicists to better understand the interactions between subatomic particles across time.

Incredibly, Feynman’s career was so prolific and impactful that at least three of his later achievements (in superfluidity, radioactive decay, and the study of quarks) might have also qualified him for the highest prize in science if he had published his research.

His relentless curiosity about the world led him to pursue a wide variety of research subjects: how friction worked on highly polished surfaces, how wind makes ocean waves grow, the elastic properties of crystals, and turbulence in gases and liquids, among many others.

Even today, decades after his death, the leading edge of physics known as “string theory” relies on his work as a foundation.

But none of the awards or accolades Feynman received can fully capture how stunningly diverse and wide-ranging his interests were. He refused to limit himself to one field, or even to science itself. He followed his passions wherever they might lead, conducting practical experiments along the way to confirm that his discoveries were valid.

He experimented for years with lucid dreaming and sensory deprivation to unravel the mysteries of consciousness. He taught himself how to play the drums, pick lock safes, draw nude figures, and decipher Mayan hieroglyphics. He embraced all of the surprise and serendipity that life had to offer with an attitude of childlike wonder.

Richard Feynman was a true Renaissance Man – as impressive as his scientific accomplishments were, what truly distinguishes him in our era of hyperspecialization is that he also managed to live a rich and varied life. His intense focus on his research didn’t prevent him from savoring the finer things in life – travel, culture, art, music, and family.

For me, this is Richard Feynman’s greatest achievement: he both went deep in the area where he could make a genuine contribution to society, while also embracing the full breadth of everything else life had to offer along the way.

Let’s take a closer look at how he did it.

Feynman’s favorite problems

Buried in an obscure article written by a contemporary of Feynman’s, the MIT mathematician Gian-Carlo Rota, lies a clue to how Feynman achieved his formidable reputation (emphasis mine):

“You have to keep a dozen of your favorite problems constantly present in your mind, although by and large they will lay in a dormant state. Every time you hear or read a new trick or a new result, test it against each of your twelve problems to see whether it helps. Every once in a while there will be a hit, and people will say, “How did he do it? He must be a genius!”

In other words, Feynman’s approach was to keep a list of a dozen of his “favorite problems” – these were fascinating open questions that he found himself returning to again and again in his research.

Here are some of the kinds of questions we know he pursued and that he might have been referring to:

- How can we measure the probability that a lump of uranium might explode too soon?

- How can I accurately keep track of time in my head?

- How can we design a large-scale computing system using only basic equipment?

- How can I write a sentence in perfect handwritten Chinese script?

- What is the unifying principle underlying light, radio, magnetism, and electricity?

- How can I sustain a two-handed polyrhythm on the drums?

- What are the most effective ways of teaching introductory physics concepts?

- What is the smallest working machine that can be constructed?

- How can I compute the emission of light from an excited atom?

- What was the root cause of the Challenger Space Shuttle disaster?

- How could the discoveries of nuclear physics be used to promote peace instead of war?

- How can I keep doing important research with all the fame brought by the Nobel Prize?

Each time he learned something new, Feynman used it as an opportunity to see if it could help him make progress on something he was already curious about. When he heard about a new finding in a research paper or a new result from an experiment, he would ask himself: Does this have any relevance to any of my favorite problems?

Most of the time, the answer was no. After all, the chances of making a connection between any two random ideas was relatively low.

But once in a while his method would strike gold. He would compare a new finding or result with one of his open questions – even if they were from completely different fields – and find a match. And the insights and breakthroughs that came pouring out as a result would leave everyone around him astonished.

Feynman worked on the Manhattan Project, the U.S. government’s secret effort to develop the first atomic bomb during World War II. Such a device had never been built before, and it required a mind that disregarded the conventional wisdom of the past.

Feynman used an unorthodox mathematical approach that wasn’t taught in any textbook to solve a key equation governing nuclear reactions. He devised a way for technicians to safely store radioactive materials (some of those technicians later believed it had saved their lives). Turning his attention to computers, Feynman helped invent a system for sending three problems at once through the rudimentary computers of the era, an early predecessor of “parallel processing.”

His approach required patience, but it had the advantage of helping him perceive connections that no one else could see. In his book Surely You’re Joking, Mr. Feynman! (affiliate link), he once noted, “My box of tools was different from everybody else’s, and they had tried all their tools on it before giving the problem to me.”

It may seem strange to label questions as “problems,” since that word usually has a negative connotation. But that is exactly what we are trying to do here – change the connotation in our minds from a negative one to a positive one.

Imagine what would be possible if we began to see the endless problems we encounter in our work and our lives as opportunities in disguise. Opportunities to learn, to grow, to change our minds, or to see things from a new perspective.

In Part 2 of this series, I’ll guide you through the process of creating a list of your own favorite problems.

A big thank you to Julia Saxena, Billy Oppenheimer, Vera Silva, Jeremy Cunningham, Luiz Eduardo, Arno Meijer, Colin Fortuner, Mike Haber, Alexandra P, Vaibhav Jain, Divyesh Pandya, Rubén García Pérez, Michael Pistorino, Ádil Bulkool Bernstein, Beth, Parisa R, and Yassen Shopov for their feedback and suggestions on this piece.

Follow us for the latest updates and insights around productivity and Building a Second Brain on X, Facebook, Instagram, LinkedIn, and YouTube. And if you’re ready to start building your Second Brain, get the book and learn the proven method to organize your digital life and unlock your creative potential.

12 Favorite Problems

How to Generate Your Own Favorite Problems: A 4-Step Guide- Posted in Creativity, Education, Goals, Habits, Personal growth

- On

- BY Tiago Forte