Building A Second Brain (BASB) is an effective default for personal knowledge management (PKM) in the digital era. But outsourcing our creative thinking to a second brain has its pitfalls.

A robust memory can be a useful supplement to digital PKM systems. Contrary to Tiago’s assumptions, memory is not a useless, outmoded relic of our biological bodies. It is an astonishing skill, and we would be unwise to overlook it.

This essay will share multiple strategies for improving our memories, including spaced repetition, memory palaces, and other techniques for improving autobiographical memory.

Why LeBron James is My Hero

I’m not a basketball fan, but LeBron James has had my attention ever since I saw him interviewed after a loss:

A reporter asks LeBron about what happened at a difficult point in the game, a seven-minute stretch during which the Cavaliers lost several points. The clip overlays game footage with LeBron’s discussion of the events, which he describes in great detail.

For me, watching basketball is a blurry game of Pong: the ball goes back and forth, back and forth, and then it’s done. This clip let me see those seven minutes from the perspective of an elite athlete who has dedicated his life to the game.

The really impressive thing about LeBron James, though, isn’t his memory for basketball. It’s actually pretty ordinary for an elite athlete to have high recall for games in their chosen sport. But LeBron remembers everything. He remembers plays other teams playing other sports made. He can accomplish similar feats for video games, recalling the plays made, how he responded, and the result. He then synthesizes that information into new strategies on the fly. He can even remember what shirt you were wearing three years ago when you last saw him.

He remembers all of this with ease—without mnemonic tricks or techniques. In other words, LeBron James is not merely an athletic, 6’8” basketball player who happens to be ambidextrous and hard-working. A virtuous feedback loop between his raw athleticism, his dedication to and passion for his game, and his gift for memory has produced an athlete superior in body and in mind.

The clinical term for such a memory is hyperthymesia, or Highly Superior Autobiographical Memory (HSAM). Clinically diagnosed hyperthymesia is very rare. LeBron’s example shows it is possible to remember far more than most of us think.

A Sane Default for Remembering

Building a Second Brain recommends that you use digital note-taking software to capture and organize notes. This approach allows new ideas and deliverables to emerge effortlessly.

BASB is based on the following assumptions:

- Our memories are limited: As humans, our memories are limited, and we often forget things: names, faces, facts, figures, concepts, etc.

- Forgetting is painful: Forgetting is often awkward, inconvenient, or worse.

- Remembering is valuable: The ability to remember what we do and learn is extremely useful and fundamental to many goals we have.

- Computers are good at remembering: Computers can store ample information with ease.

- Brains are good at connecting: By storing relevant and interesting information in digital notes, we can use our native strength as humans – making intuitive connections between previously unrelated ideas.

Based on these assumptions, BASB recommends that you use the right tool for the job. Use computers to store information in the form of digital notes, forming a “second brain.” Use your “first brain” to handle pattern recognition and make unexpected connections between ideas.

BASB is the best system for digital knowledge management that I’ve found. Regular and consistent use of my “second brain” has been joyful, profitable, and world-expanding in the best possible ways, and I’d recommend it to anyone.

However, I disagree with the first assumption listed above, that our memories are limited. We do forget things, and it is mentally taxing to recall things, but as we have seen, it is possible to remember far more than most people think.

Memory is like a muscle. It makes sense not to strain our muscles, and BASB lets us avoid doing that with our memory. But we shouldn’t let our capacity for remembering atrophy either. Having built a trustworthy second brain, we should strengthen the native memory muscles of our first brains. So while BASB is a system for remembering valuable information, it makes sense to complement it with other strategies.

Spaced Repetition

The main contemporary competitor to Building a Second Brain is Spaced Repetition Software (SRS), such as Anki. It takes advantage of something called the forgetting curve. This graph predicts when we will forget new information. SRS uses an algorithmic approach to match this “forgetting curve,” so that you can review new information just before you forget it, for optimal long-term memory storage.

The practical implications? Spaced repetition can help you remember anything, forever. If you enter a fact you’ve learned into a spaced repetition system, and faithfully review your cards daily, you will end up committing that fact to long-term memory, and you will have spent very little time doing so.

I’ve used Anki extensively in the past. I used it to pass Ancient Greek in college. Rather than flunking out, I remembered obscure words my peers had forgotten.

I used Anki to complement my studies of programming by memorizing functions in programming languages, and keyboard shortcuts in my editor, Emacs. I became increasingly fluent in my chosen programming languages, to the point that I could get a job programming in one of them, despite having no formal training.

I also used Spaced Repetition for more trivial pursuits, like memorizing flags, geographical facts, people’s names and faces, and birthdays.

In my first conversation with Tiago, I asked him about spaced repetition software. At that point, SRS was the best-in-class personal knowledge management solution I had found, and I was thrilled that it existed.

Tiago’s reply astonished me:

His stated goal was to memorize as little as possible:

This astonished me. I wanted to memorize as much as possible – something SRS had helped me to do easily – and here was someone saying he wanted to memorize as little as possible.

After following Tiago’s work for several years, and taking his Building a Second Brain course, I see the value in PKM. And it’s easier now to see the problems with SRS. For starters, I found SRS to be emotionally exhausting. I experienced intense burnout and motivation issues every time I sat down to review my cards. From conversations with others who use or have used SRS, I’m not alone. It takes a lot of time, effort, and willpower.

I also believe that SRS is widely misused:

- People use SRS to learn information, rather than remember it: Once you’ve learned a new fact – such as that “tiga” is the word in Bahasa Indonesia for three – SRS will help you to remember that fact. SRS is not well-suited to helping you learn information. It’s for remembering information you’ve already learned.

- People don’t read the manual: It’s worth taking the time to read the manual for your SRS tool of choice, and learn how to use its features effectively. If you don’t, you may take a suboptimal approach and waste your time.

- People use others’ flashcards: In my experience, shared decks of flashcards are of such poor quality that it’s not worth using them. Besides, making your own deck is a reward in itself for memory. If you do use others’ decks, download them and suspend them, curating and adapting them as needed. You may need to change the structure of the information entirely (e.g. from front/back to a custom format for that information). This curation is extremely time-consuming, and probably not worth doing.

- People use it to remember too much and/or the wrong things: With Anki, it suddenly becomes possible to remember any fact you want. This includes obscure film trivia, esoterica of ancient software, and other practically useless information. Just because you can remember something, doesn’t mean you should.

SRS is like a sharp knife. SRS is extremely effective at helping you to remember information. It can more or less guarantee that you will remember important facts when you need them. But it is also very easy to waste your time by remembering information that you don’t really need, or taking a suboptimal approach because you don’t fully understand the software.

Tiago’s criticisms of Anki and SRS helped me to see these problems. But having taken the course and drank the Kool-Aid, I would politely disagree with Tiago. Tiago said that SRS doesn’t make sense. I still think that there is a place for spaced repetition software like Anki: as a complement to BASB.

Here are my current, highly limited criteria for using SRS. SRS might be the correct approach if you are learning something that is:

- extremely fact-intensive

- very important (actively relevant to your current responsibilities, goals, and long-term vision)

- where easy recall will dramatically improve your outcomes (compared to using reference materials, notes, internet search, etc.)

For example, foreign languages are an excellent use case for SRS, if and only if they are relevant to your current responsibilities, goals, and long-term vision. If you’re simply taking a course out of a sense of obligation, it’s probably not worth the effort. But if you want to speak your long-term partner’s native tongue, you will find it extremely helpful (but not sufficient).

Outside of this narrowly defined scope, you don’t want Anki to be the cornerstone of your PKM. Use BASB instead. If you decide to use SRS, keep it relevant and related to your goals. If it stops being fun to review your cards, listen to the wisdom (and boredom) of your body, and move on.

Traditional Mnemonic Techniques

Like us, ancient civilizations were deeply aware that our memories are flawed. But they took a very different approach to solving the problem. The ability to memorize information – poems, events, people, ideas, etc. – was considered a moral virtue. Practicing memorization was thought to build character.

With these values, ancients developed incredible ways to memorize in efficient, effective ways.

There are many “mind hacks” for extending our first brain’s memory capabilities, using our first brain alone. One of the most famous mnemonic tools is a memory palace.

Memory palaces take advantage of the fact that our memories work very well on “location data.” It’s easy for you to remember the details of your childhood home, for example, even if it’s been years since you’ve been there.

To create a memory palace, pick a location you know well to use as the palace. Then you need to define a route to “walk through” the palace with. When you use your memory palace, you should always store memories in the same order. For example, I use my childhood home, and walk through the laundry room, then the dining room, then the kitchen, then the family room, then into my bedroom, and so on.

When you want or need to remember a series of related things, like verses in a poem or your shopping list, you place the items or ideas in memorable ways along the path in the memory palace. Like it or not, the brain remembers things that are funny (awkward situations), crude (sex acts, toilet humor), or unusual (multi-colored elephants). Try to link what you need to remember (“blue napkins”) to one of those things (“someone wrapped in a giant blue napkin on the laundry machine”). Between the extreme quality of the memory and the location it’s stored in, you’ll find that it will be far easier to recall than it would otherwise be.

I make use of these memory palaces frequently, as a complement to other memory storage devices. I tend to use them when I don’t have access to a capture device (notebook or smartphone), or can’t use one (when in conversation, or driving). In my line of work, training intensively at the Monastic Academy, I most often use them when meditating in a space where others are sitting quietly.

I often think of tasks I need to do, or new project ideas, when on the meditation cushion. It takes me about two to four seconds to come up with a memorable image related to the task, store it in the next location in my memory palace, and return to my meditation technique. Doing so lets me “record” the task with minor disruption to others in the room and my own meditation practice.

When I next have the ability to edit my task list, usually within twelve hours, I capture all the items in my memory palace and then “clear” the palace of the images I stored there.

As with SRS, don’t use mnemonic techniques to memorize everything ever. Be familiar with them, and learn how to use them, but use them judiciously as secondary tools where appropriate.

Mindful Review

SRS and traditional mnemonic techniques are both excellent, but they are most useful for concrete facts and concepts, like a foreign vocabulary word or the capital of a country. They don’t necessarily improve the kind of memory that LeBron excels at: autobiographical memory.

It is possible to improve our memory for “life events” as well. I’ve found two techniques for doing so. Because they have to do with our own phenomenological experience, both techniques are essentially meditation or mindfulness techniques. The first technique is called Mindful Review.

The purpose of Mindful Review is to review (or remember) recent events that happened to you, and make use of them.

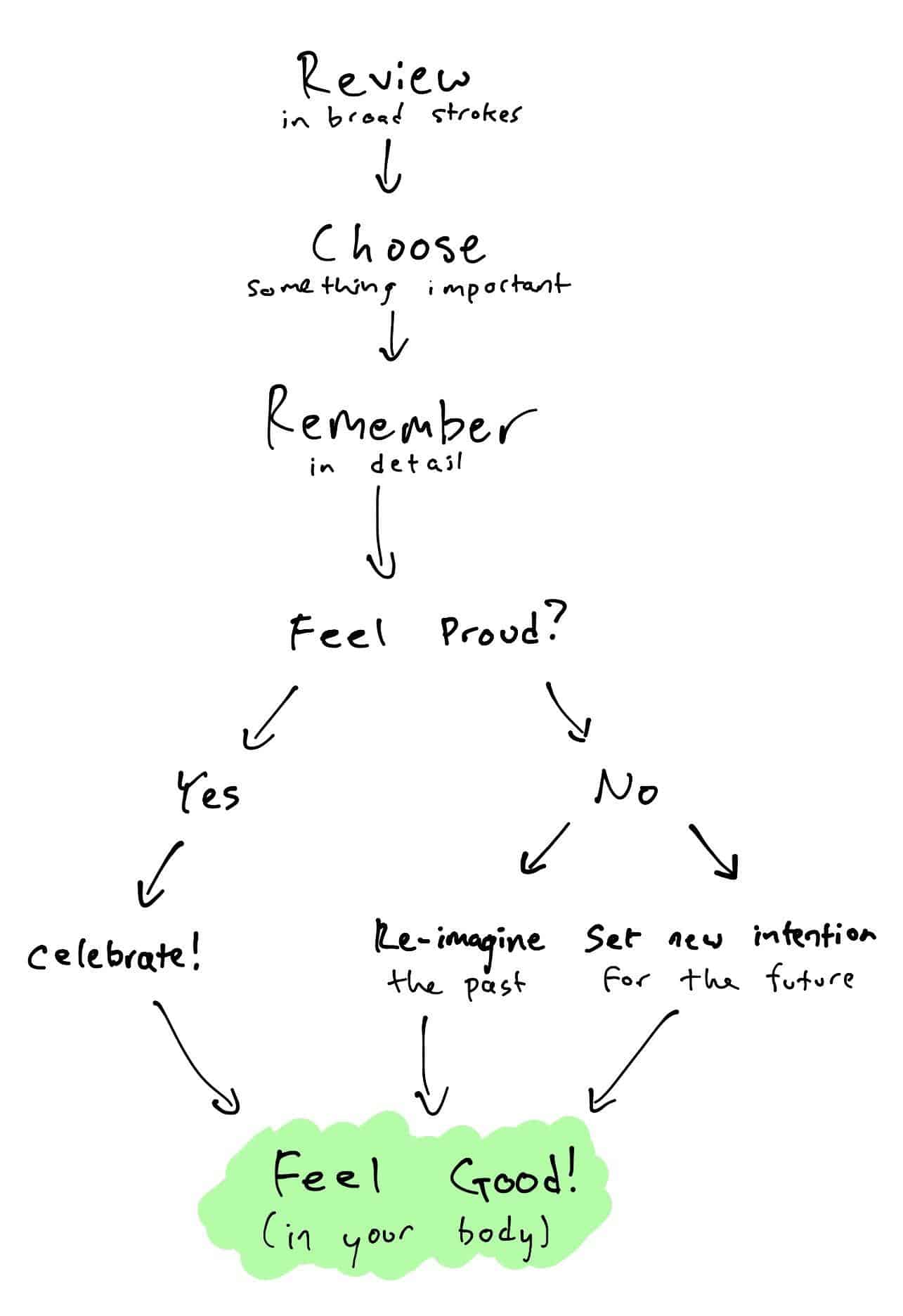

Here’s how I practice Mindful Review:

- Review your recent actions, recollecting the last day or so in broad strokes.

- Choose an event that seems important – one you might be proud of, or not so proud of, or simply an ambiguous event you’d like to explore.

- Review this event by remembering it in as much detail as you can. Remember the area around you, how mindful you were (or not), what happened in your body, what you saw and heard, how you felt, what others may have said, their body language, etc.

- If you feel proud of what happened, celebrate that! Commend yourself mentally. Say, “that was good! Nice work!” or something that resonates with you. Bask in any feelings of pride or joy or pleasure that arise. Explore and enjoy these positive emotions.

- If you don’t approve of what happened, you can also turn this into a positive experience. You can envision having done it differently in the past, or set a different intention for the future.

- Either way, feel good. Feel good in your body. In this way, we learn to celebrate and grow our successes, and learn from our mistakes – so there’s always a positive outcome.

You can stop there, or you can repeat this process with as many discrete events as you like. If, during the session, you think of something concrete to do as a result of this meditation (like offer an apology), follow up on that.

Mindful Review works best when done regularly, ideally daily. If you practice it consistently, you will start to see incredible behavior changes over time. Some of these changes will be small, and some will be big. Either way, they will make a meaningful improvement on your quality of life.

And, for our purposes, your recall of recent events will improve dramatically. You will be increasingly able to remember the past day or so in extreme detail.

Calendar Memory

In 2012, someone with the handle Lembran Sar started a blog called Lembransation, dedicated to their exploration of a rather unusual memory technique. The author reports that they can currently remember seven years of memories.

The technique has two stages: a curation stage, and a review stage.

- Curation: Each day, you pick an image of what happened that day, and associate it with that weekday and calendar date. For example, on Saturday, March 2nd, 2019, I chose a memory of playing a game with my Dad.

- Review: You periodically review all of the images. At minimum, you do a review each day of all of the images from that month; your image of what you were doing on the same day of each month for the previous six months (e.g. February 2nd); finally, you review what you were doing on the same date for the last year(s) before (e.g. Friday, March 2nd, 2018).

I’ve done this technique for several months at a time, although I’ve currently paused my use of the technique. I know someone who has done this technique for a year and a half, and Lembran Sar has been doing the technique for seven years and counting. In my experience, it only takes 1-5 minutes a day. Your memory improves dramatically, the information comes in handy from time to time, and it’s a lot of fun.

I’ve done extensive work on my autobiographical memory of daily events by using Mindful Review. All that work came in handy with this technique. Recalling a chosen piece of a given day almost always brings back a flood of specific details from the day.

It’s easy to create a positive feedback loop between this technique and mindful review. The more you want to remember calendar days, the more you want to remember details, and vice versa. The more you want to remember something, the more you do. So if you do both techniques, you end up remembering larger and larger spans of time with more and more detail.

My long-term goal for using these techniques is to be able to recount precise words I or others said in conversations. This effectively means being able to recall entire conversations verbatim. This requires a high degree of skill, but everything I’ve seen from my experiments with these techniques suggests it’s possible. I have some practical reasons for wanting to be able to do this: my meditation teacher suggested it as a goal to strive for; it’s useful to be able to recall conversations in detail; it requires a high degree of mindfulness and concentration. But above all, it seems like a fun challenge.

Which technique to use?

This article has presented several different approaches to augmenting human memory. Each system has strengths and weaknesses. You shouldn’t necessarily use every tool available to you – rather, learn to use the ones that seem relevant to your purposes.

- Use Building a Second Brain and digital note-taking as a default system for capturing, organizing, and using information.

- Use Spaced Repetition software like Anki for fact-intensive information that is very important; highly relevant to your current responsibilities, goals, and long-term vision; and where easy recall will dramatically improve your outcomes (compared to using reference materials, notes, internet search, etc.).

- Learn to use mnemonic techniques like memory palaces and the Major System to exercise your memory. Apply them to your life and work if it seems fun, useful, or interesting.

- Use Mindful Review for short-term autobiographical memory to improve your mindfulness and ethics.

- Use Lembran Sar’s technique for long-term autobiographical memory.

Conclusion

LeBron’s memory has helped him to become one of the world’s most accomplished athletes. His example demonstrates that it is possible to create a positive feedback loop between athletic skill and accomplishment, intellectual capacity, and attentional skill. This is the same feedback loop that I have referred to as Mind, Body, Attention.

LeBron is also a devoted philanthropist. One of his most famous projects is creating a school which is changing how educators think about providing services to at-risk youth. To me, this is a clear example of how excellence in Mind, Body, Attention can strengthen our sense of responsibility in the world. In turn, that compassion for the world can support us in deepening our own contemplative practice.

I don’t admire LeBron James because I want to become one of the world’s best basketball players. I want to develop skill in as many aspects of my life as possible, and integrate them into one seamless feat of excellence. And, as someone who has taken bodhisattva vows, I aspire to emulate LeBron in this way not for its own sake, or for my own glory, but for the benefit of all living beings.

Further Reading

Spaced Repetition

- Want To Remember Everything You’ll Ever Learn? Surrender To This Algorithm

- Effective learning: Twenty rules of formulating knowledge

- Leitner system

Mnemonic Techniques

- Joshua Foer’s Moonwalking with Einstein (notes)

- A Master of Memory in India Credits Meditation for His Brainy Feats

- The Major System, an interactive essay

Mindful Review

- Catalyzing Positive Behavior Change with Mindful Review

- Upasaka Culadasa’s The Mind Illuminated, Appendix E

Calendar Memory

- Lembransation (notes)

- A Case of Unusual Autobiographical Remembering

- Total recall: the people who never forget

Follow us for the latest updates and insights around productivity and Building a Second Brain on Twitter, Facebook, Instagram, LinkedIn, and YouTube. And if you're ready to start building your Second Brain, get the book and learn the proven method to organize your digital life and unlock your creative potential.

- POSTED IN: Building a Second Brain, Guest Posts, Note-taking