I believe that moods (or less colloquially, states of mind) can be used not just defensively, making the best of whatever mood you’re in (as I described in Productivity for Precious Snowflakes).

They can also be used offensively, to proactively create the conditions for rapid acceleration and value creation.

Let’s begin with a simple question: why do we have moods?

It’s not an obvious one. You would think that not having moods — simply doing whatever is the next thing that logically needs to be done — would have given our ancestors a decisive evolutionary advantage. Fast forward to today, many people seem to think that banishing their moods and suppressing their emotions would give them a superhuman ability to get things done.

An intriguing answer is suggested by this paper: that the function of moods is to represent momentum in the mind.

Let’s look at an example. Let’s say you are a small squirrel-like creature sometime before the last ice age. You find some fruit on a tree, a rare and precious source of sugar and carbohydrates. Then you find a second tree with fruit, and a third in quick succession.

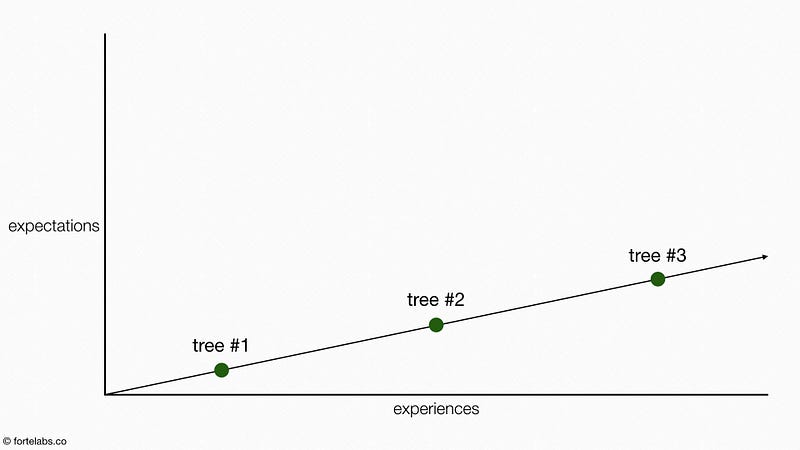

If you had no moods, and processed new information using pure logic, you would update your expectations of the trees one at a time. You wouldn’t make any unjustified assumptions about future trees based on past experience. Finding fruit on three trees in a row would increase your expectations of future rewards linearly:

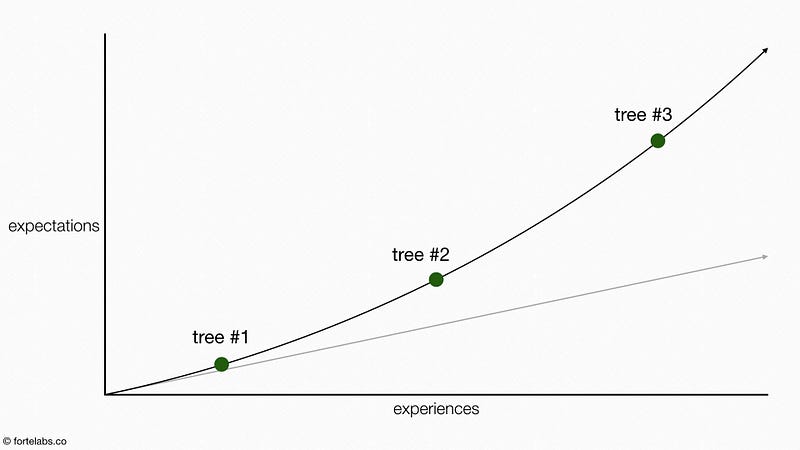

But this is actually not optimal, because in nature, sources of reward are correlated: they tend to rise and fall together. If there is extra rainfall or extra sunshine, all the trees in an area are likely to produce fruit at the same time. It makes more sense to increase expectations exponentially, for all the trees in the area, even though you only have a few data points.

Why? Because the organism who increases its expectations more quickly will act faster to take advantage of favorable environments, which tend to be temporary. There is a limited amount of time to eat the fruit before it’s gone.

This extrapolation is the function of moods. Our squirrelly friend finds one piece of fruit, and is happy. It finds a second one, and experiences a disproportionate jump in happiness. Two trees in a row?! It finds the third one, and by this point is positively ecstatic. A series of surprises in close succession causes the animal’s expectations of even more fruit to skyrocket, putting it “in the mood” to drop everything and find as much fruit as possible, before it rots.

Our moods are extrapolation engines, putting us in the appropriate state of mind to take advantage of fleeting opportunities, without having to wait for full information. You can think of a given state of mind as a temporary bias, increasing our sensitivity and responsiveness toward a certain kind of reward that seems to be in unexpected abundance.

In this way, our moods allow us to infer changes not only in individual sources of reward, but in overall trends and fluctuations in our environment, which allows us to commit to a course of action and act more quickly.

Pretty amazing, huh?

This would explain why “fake it till you make it” works in a wide variety of situations. By taking some action, however superficial or insecure, you “prime the pump” of your emotions by generating unexpected rewards (a public speech going better than expected, for example). These emotions put you in the mood to be more sensitive to any further rewards, which prompts more action to seek them out. Action primes emotion, and then emotion primes further action.

Bringing this to the modern day, one of the most compelling recent advances in the study of human motivation has been the field of Psychological Capital (PsyCap for short). As this paper describes, PsyCap proposes that humans have “reserves” of psychic resources, specifically, hope, resilience, optimism, and efficacy. These reserves are state-like (as opposed to trait-like), and thus can be understood, learned, and developed. The authors note several studies showing a strong correlation between these states and work performance and satisfaction.

Taken together, these psychic reserves can be described as follows:

Psychological Capital: one’s positive appraisal of circumstances and probability for success based on motivated effort and perseverance.

This is a remarkable definition. First, it claims that the amount of “reserves” we have at any given time is primarily a result of our perception (appraisal). This would imply that we can increase our psychological capital just by seeing things differently.

Second, it is not only our perception of “how things are going” (real circumstances) that matters, but our expectation of “how things will probably go” (probability of future success). As we saw previously, this expectation is represented in the mind by moods — when you’re in a bad mood, you expect everything to go terribly. When you’re in a good mood, you expect everything to be great.

What this means is that we don’t have to “convince” our rational minds that the future is rosier than we think. That is a futile undertaking anyway, since it is difficult to use the rational mind to convince the rational mind of anything. Instead, we can change our expectations of the future at a more fundamental level, by creating a series of unexpected rewards to prime more positive moods, essentially “faking” momentum until it becomes real.

Besides obvious methods like taking a break, getting some sleep, eating a good meal, or spending time with loved ones, how can we design our work to take advantage of this phenomenon?

Positive psychologist Csikszentmihalyi noted that psychological capital “is developed through a pattern of investment of psychic resources that results in obtaining experiential rewards from the present moment while also increasing the likelihood of future benefit.

In other words, we can create the perception of momentum by 1) structuring our work to produce experiential rewards now, and 2) completing our work in such a way that it increases the likelihood of benefit in the future.

This creates a positively sloping and exponential line, each day reaping the rewards of past work sessions, enjoying the present activity, and laying the groundwork for future activity. It’s like compounding gains in investing, but for productivity:

Before looking at some practical examples, there is one final missing piece, provided by a third paper on a theory known as the Goal Gradient Hypothesis (explained briefly in this Farnam Street article). The idea is simple: we speed up as we get near our goal, and then slow down afterwards. This is as true of rats in a maze, as humans approaching a deadline.

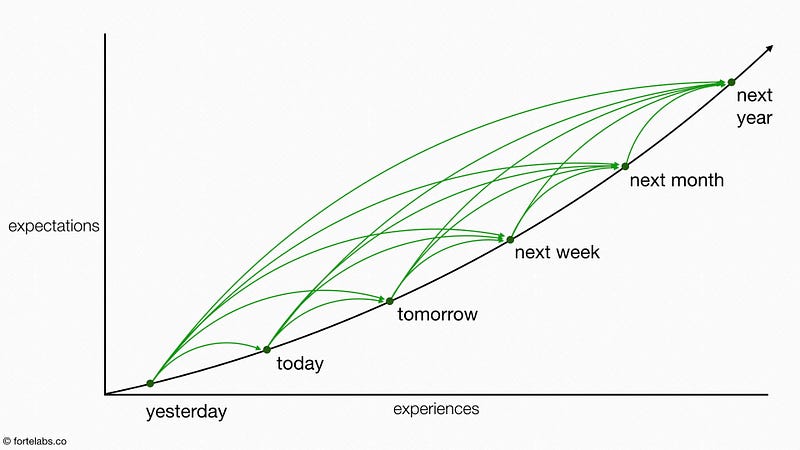

This theory adds another element to our framework: the “sources of reward” have to come quickly, one after another in rapidly accelerating succession, to have the psychological effect of creating momentum.

The modern workplace is not designed with this need in mind. The productivity of everyone in the company is optimized not at the level of the individual, but at the level of whatever the company sells and whatever gets measured on the balance sheet: deliverables, projects, products. While this is necessary for business performance, the pace of progress and delivery on big projects with many collaborators is nowhere near fast enough to provide a sense of increasing momentum, which may explain why everyone working on such projects tends to be in a bad mood.

But this problem is not exclusive to large organizations or large projects. Even deliverables produced completely by a single person progress too slowly — we need rewards on the level of minutes, not days or hours.

This is why I put so much emphasis on designing individual, intermediate packets of work. These are units of work smaller than deliverables — digital notes, work-in-progress drafts, outlines, brainstorms, checklists, etc. For most people, this information tends to remain in a state of total chaos, if it’s preserved at all.

Take my notes on the Farnam Street article above as an example. It’s a short article, but stopping my writing for several minutes to re-read this source, of which only a tiny portion is relevant to my needs, would be like a speed bump in my subjective enjoyment of writing this article. Now imagine the three academic papers I’ve incorporated. Having to re-read those would be like brick walls when it comes to momentum and motivation.

By taking the time previously to summarize these notes in multiple layers, I’m lowering the transaction cost of pulling these sources into my writing in the present. Lowering the transaction cost — the friction — makes the rewards of writing come more quickly, which creates a feeling of momentum that makes the experience more intense and enjoyable. I’m combining distillation and random access — concentrating the insights from a period of months down into a dense pool of explosive inspiration triggers at my fingertips.

What’s been most surprising about this method of Progressive Summarization is that it’s not just about having an iron will to delay gratification to some unknown future date. Summarizing sources is gratifying now, because it changes consumption from a passive process of questionable future value, to an active process I know will provide value in the short, medium, and long term. By creating benefits both now and in the future, I’m building reserves of hope, resilience, optimism, and efficacy — I’m building psychological capital. Work becomes intoxicating when you have the confidence that everything adds value, and everything will eventually get used.

Besides designing packets of work in this way, to have clear “handles” to be easily picked up later, there is another technique I’ve noticed that can be used to create that initial burst of acceleration to get things moving: mood accelerators.

I first saw it articulated in this short essay by John Perry, a philosophy professor at Stanford, who later turned it into a book. To summarize, Perry argues that procrastination has been one of his most useful productivity tools, insofar as he’s used it in a structured way. Essentially, he always has one intimidating task with a looming deadline at the top of his to do list. He uses his aversion to starting this task as a source of energy to accomplish a whole range of apparently less important, but still worthwhile tasks.

Perry notes that chronic procrastinators often mistakenly follow the opposite approach: they minimize their commitments, thinking that if they put in front of them only this one, big, important task, they will stop procrastinating and be able to force themselves to do it. But this just makes that task even more intimidating and threatening, activating all the resistance and avoidance mechanisms that procrastinators know so well. They leave themselves with much less desirable alternatives: doing nothing, or something not even a little productive.

For procrastinators (by which I mean, everyone), their most important source of motivation is avoiding the thing they should be doing. They possess the energy and intuition of an escape artist, which require something to escape from in order to be utilized effectively.

Although I find this brilliant, it points to a deeper principle: emotions contain tremendous energy. For all the talk about the importance of sleep, exercise, a good diet, and rest, I believe that all these pale in comparison to the energy made available by our emotions. Some of my most productive days ever lacked sleep, healthy food, or exercise, but kept me going with the excitement of a new idea or approaching milestone.

Here are some other ways I’ve found of using the energy of emotions to my advantage:

Cancelled appointments

I like many others feel a rush of relief when an appointment or event I’m not looking forward to gets cancelled. I can use this rush of positive energy to complete a new deliverable, which I also now have the time for. Sometimes I even schedule things I secretly know I’m not really going to, just to provide a little bit of that energy.

Repressing things I want to do

I’ve found that, by delaying working on something I’m extremely excited to work on, the energy behind it gathers, like a pot pressurizing the steam within. Delaying the start of such a task by a few days gives me a store of energy that I can unleash when I actually do get started.

Accumulating a large batch of small admin tasks

One of my greatest challenges has always been finding the motivation to do all the little administrative tasks that accumulate in any person’s work. I find that by storing them up over the course of a week, and doing them quickly in one big batch, I can create the series of accelerating rewards that the tasks themselves lack.

Having a theme song for each project

This evolved naturally, but I’ve found it very helpful to have a “theme song” for every project I take on. Playing the song immediately allows me to “pick back up” the state of mind I was in last time I worked on it. I don’t play it on repeat like some people, but any time I get stuck, the project theme song usually helps me remember a previous jumping off point that provides a new path forward.

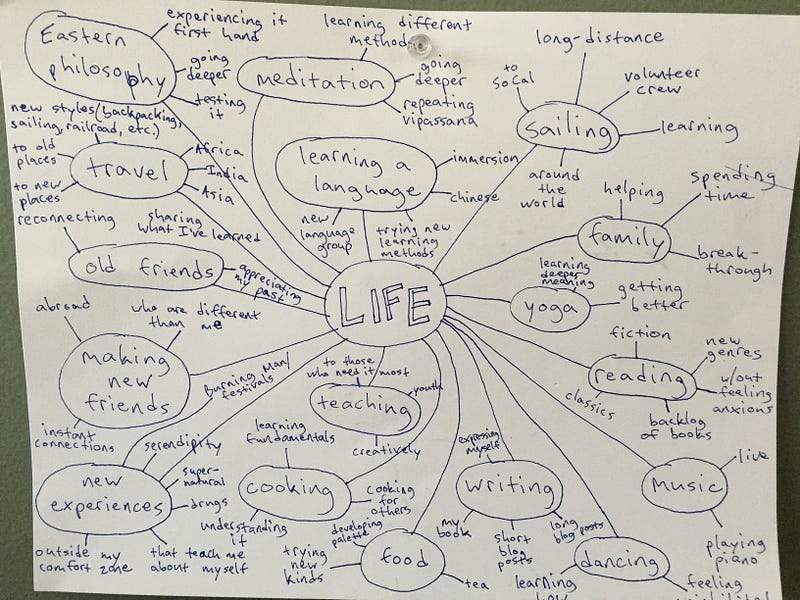

Make an Excitement Map

This is an exercise that, as far as I know, I invented as a way to remind myself of what I’m excited about. It is easy:

- Make a bubble in the middle with “Life”

- Branch out from there with bubbles containing each aspect of life that you’re excited about

- Branch out from those bubbles answering the question “Why am I excited about this?” or “What specifically about this excites me?”

I’ve found this to be a powerful way of connecting to what really matters to me in my life.

Live-tweeting book notes

Probably my favorite example, which I talk about in my online course Building a Second Brain, which kicks off on July 17th with version 3. It’s a practice I’ve developed of turning my book notes into external knowledge artifacts that can be shared. Here’s an example, from my notes on the book Toyota Kata.

I read a book, and take conventional notes on the parts I find interesting or insightful, saving them to Evernote. I then progressively summarize those notes, adding bold, yellow highlights, a bullet-point executive summary, and my own commentary in successive layers. When the notes are maximally summarized in this way, and I’m already reviewing them anyway for a project, I’ll live-tweet the process of reviewing my own notes. I don’t usually tweet the exact phrases, but rather my thought process as I’m reading them. I’m riffing on what the ideas bring up for me, in real time to my Twitter followers, in a series of numbered tweets known as a “tweetstorm.”

This has several powerful effects. First, knowing that I will share these insights in the near term holds me accountable to taking good notes in the first place. This gives me the motivation to transcribe notes from difficult sources like podcasts, audiobooks, and PDFs. Second, knowing that people will see my summary without the original context forces me to explain it very clearly, which helps me understand it myself. Third, I get feedback on how interesting or impactful the ideas are, on a sentence-by-sentence level. And fourth, I gain a loyal following, because there is so much insight condensed into each tweetstorm. I actually create the impression that I am much smarter than I am, because everyone assumes I’m just dashing off my idle thoughts, not following a multi-part workflow.

These tweetstorms I believe led recently to my inclusion in this list of 82 Startup Founders, Execs, VCs, And Reporters To Follow On Twitter (even though I am none of those things — go figure).

The experience of tweetstorming itself is also a lot of fun, because I’m rushing to get my thoughts out before people respond with their opinions and objections. There’s a sense of creative risk-taking, which promotes flow, because I don’t plan them out in advance, and have to build the logic on the fly. It’s so exciting that I have to refrain from tweetstorming before going to bed, because I’ll be too worked up to sleep!

Earthquakes

I previously highlighted this quote from Josh Waitzkin:

“In performance training, first we learn to flow with whatever comes. Then we learn to use whatever comes to our advantage. Finally, we learn to be completely self-sufficient and create our own earthquakes, so our mental process feeds itself explosive inspirations without the need for outside stimulus.”

I’ve been on a journey to discover what that third level of performance looks like in modern knowledge work. Mood-First Productivity, and in particular structured procrastination, mood accelerators, intermediate packets, and progressive summarization, are the best ways I’ve found to “create my own earthquakes.” These methods rely on the understanding that human creativity and motivation are driven primarily by emotions and moods, not cold, calculating logic.

This is why personal growth is inextricably tied to productivity. Like emotion and action, each primes the other. Recruiting the power of emotions is not a matter of productivity tips and hacks. It takes deep self-awareness, intimate knowledge of the unique landscape of your internal mental environment. Exploring this landscape requires vulnerability, authenticity, self-expression, and sharing, not just study.

Follow us for the latest updates and insights around productivity and Building a Second Brain on Twitter, Facebook, Instagram, LinkedIn, and YouTube. And if you're ready to start building your Second Brain, get the book and learn the proven method to organize your digital life and unlock your creative potential.

- POSTED IN: Cognitive science, Emotions, Flow, Note-taking, Productivity, Time management, Workflow