Knowledge work is unique among skilled professions in that we lack a culture of systematic improvement.

Other skilled trades – from carpenters to welders to nurses to pilots – have been around long enough and are repeatable enough that the best practices are widely understood.

How to frame a door, how to weld a seam, how to prepare an IV, how to prepare for landing – these tasks aren’t a mystery. Other professions have developed training over time to teach every novice how to master them.

But the same isn’t true of most knowledge workers. We receive precious little training in how to “do” knowledge work. There is no class in college on how to triage your email inbox, manage your agenda, or organize your computer files. And the situation doesn’t improve when we enter the workforce: most employers don’t teach us how to formulate goals, document our knowledge, or automate our most common tasks.

We spend tens of thousands of dollars on our education, plus thousands of hours learning specialized skills. Yet so little time and effort is spent mastering the most fundamental skill of all: how to manage our work.

To develop a culture of systematic improvement, it’s not enough to have inner discipline. We also need to follow an outer discipline – a system of principles and behaviors – to channel our energies, thoughts, and emotions productively. A system that adds some structure to the constantly changing flux of information that we interact with every day.

One of the closest parallels for what we are looking for can be found in mise-en-place, the respected culinary tradition used by chefs in commercial kitchens around the world.

Like us, chefs only have so much energy and working memory at their disposal. Chefs use mise-en-place – a philosophy and mindset embodied in a set of practical techniques – as an “external brain.” It gives them a way to externalize their thinking into their environment and automate the repetitive parts of cooking so they can focus completely on the creative parts.

I recently dove deep into the workings of mise-en-place as described in a book called Work Clean (formerly titled Everything in Its Place), by Dan Charnas (a more recent edition is available in softcover, hardcover, and audiobook formats only).

In this article, I’ll summarize what I believe to be the most important lessons we can immediately put to use in knowledge-intensive work today.

What is mise-en-place?

Mise-en-place has its origins in 1859, when a 13-year-old boy named George Auguste Escoffier started working in his uncle’s restaurant in Nice in the south of France.

By the time he died at age 88 in 1935, Escoffier had transformed French cuisine into the global standard and elevated the work of a chef from manual labor to something approaching artistry.

One of Escoffier’s main influences was his time in the military, and this is reflected in the strictly defined roles he created for the kitchen: the chef de cuisine was the commanding officer; underneath him were his lieutenants the sous-chefs; and underneath them were various chefs de partie who ran the various stations, including garde-manger (pantry), sauté (range cooking), saucier (sauces), patissier (desserts), rôtisseur (roast or grill), poissionnier (fish), and friturier (fryer).

These positions made up the culinary equivalent of a high-volume manufacturing assembly line. Each ingredient, tool, and dish flowed according to a precise plan. And this plan continues to govern how kitchens operate in restaurants around the world to this day.

Mise-en-place is about bringing together all the tools a chef needs in close proximity, prepped for immediate use, so that they can just execute – quickly, consistently, and sustainably. It is a multi-faceted system that includes:

- A philosophy – what chefs believe

- A standard of excellence – what chefs adhere to

- An arrangement of ingredients – how chefs set up their environment

- The practices of cooking – how chefs cook

- A mindset – how chefs think

All these facets of mise-en-place can be distilled down to just two words: work clean. Clean as in efficient. Clean as in elegant. Clean as in direct. Clean as in without friction. Clean as in simple. Clean as in clear. Clean as in decisive. Clean as in powerful.

What can mise-en-place teach us?

The broad field of knowledge work is in a similar place today as the craft of cooking was in 1859.

Our labor is difficult, but undervalued. We spend way too much time thinking about how to get things done, versus doing them. We approach each new task and project as if it was a completely blank slate, requiring an entirely new approach.

Our careers as knowledge workers are starting to look a lot like chefs – non-linear, itinerant, based on gigs, demanding flexible collaboration with a constantly changing group of collaborators.

We likewise have to contend with a deluge of tasks, under uncertain conditions, with tight deadlines, using tools and resources that weren’t always built for the task. We also receive a constant stream of inputs and requests, have too little time to process them, and face many demands requiring simultaneous attention.

And at the end of the day, we also have to deliver tangible outputs, at an extremely high standard of quality, to a large number of customers and other stakeholders. It’s time that we had a working system for the mass production of high-quality knowledge work, in the same way that chefs rely on mise-en place.

There are 6 practices that mise-en-place has to offer us:

- Sequence

- Placeholders

- Immersive vs. process time

- Finishing mindset

- Small, precise movements

- Arrangement

It is not enough to “get organized” and find the “right place” for everything at one point in time. We need a dynamic, flexible system that allows us to continually access what we need without throwing our environment (and mind) into chaos.

These practices form a holistic system – not just for being clean, but for working clean.

The 6 Practices of Working Clean

1 – Sequence

In a kitchen, sequence is everything.

The biochemical realities of food demand it: the meat can’t go onto the chopping block if it’s frozen; the pasta won’t absorb the sauce unless it’s been cooked; the garlic can’t be added until it’s been chopped.

In knowledge work, the importance of sequence isn’t always so clear. Does it really matter whether you send that email or write up that report first? It often feels like we should be doing everything immediately and all at once.

But consider that we can never do more than one thing at a time. The flow of time is linear, which means at some point, even our most complex thinking and planning has to get distilled down to a simple, linear to-do list: what comes first, what comes next, and what comes after that.

Once we realize the importance of sequence, it becomes apparent that not all moments are created equal: the first tasks matter much more than the later ones. In a kitchen, the few seconds it takes to start heating up a pan or start defrosting the chicken will have the biggest impact on the overall timeline, because these steps can’t be accelerated. They take as much time as they take.

Likewise, in knowledge work, the first tasks matter the most. The first acts of your morning will set the direction of your entire day. The first thing you do when starting your workday will set the tone for everything that follows. Even on the scale of a single hour-long working session, the ideas you color your mind with at the start will flow downstream to every other decision you make.

The present has incalculably more value than the future. Because the actions you take right now have more time for their effects to propagate. A minute spent now could save you hours tomorrow. An hour spent today could save an entire day compared to waiting until next week.

It’s worth making a to-do list, but not because you can predict exactly how your entire day will go. And it’s not because you know for sure you’ll get to everything on it. You make a to-do list to decide how the sequence of actions you are committing to will begin.

2 – Placeholders

For a chef, every physical object serves as a placeholder.

The first action a chef will take is often to set a pan on the stove and start heating it. That pan isn’t just a pan. It is also a placeholder reminding him that a dish is in process. The sizzling of the oil is the alarm bell cueing up the next step.

Such actions are called “first moves,” and they become especially important when multiple requests arrive at the same time. What is a chef to do if three things are asked of her at once? She can’t write anything down, and doesn’t dare rely on her memory.

The chef externalizes those reminders into her environment – placing a pan for preheating, setting a bunch of parsley on the cutting board, or putting out a sauce pan for example. Each of these physical items represents the starting point for a stream of actions she’ll need to take. And she can recall all of them with just a quick glance around her.

As knowledge workers, our situation is even more dire. In any given hour, we might receive ten times more requests that we can even consider. They are streaming in 24/7 across dozens of communication channels.

Thus our first moves are even more important. Every time we capture an “open loop” or save a digital note, we are placing artifacts in our environment to serve as reminders. Since so much of our work is digital, it makes sense that these artifacts are digital as well.

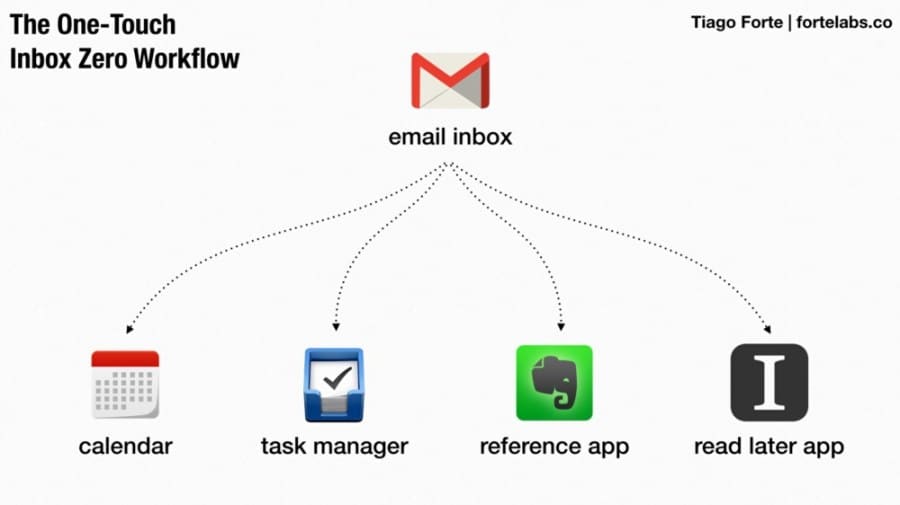

As I explained in One-Touch to Inbox Zero, we can use a small set of free digital tools, including a task manager, digital notes app, read later app, and online calendar, to create an environment that “remembers” everything that needs to be done.

Every incoming input – whether it comes from a new email or a spontaneous thought in your mind – should trigger an immediate “first move,” which could include adding an appointment to your calendar, capturing an open loop in your task manager, creating a digital note, or saving an item to read later. Each of these items serves as a reminder of an action you might want to take, and they are all preserved in a trusted place outside your head.

3 – Immersive vs. processing time

The biggest constraint for a chef is time. They can stockpile and prepare any number of seasonings and ingredients, but time always flows at its same, never-changing pace.

But not all time is created equal. There is an important distinction for chefs between two different kinds of time: “immersive” versus “process” time.

Immersive time includes tasks that require the chef’s full focus and involvement. Stirring, sauteeing, mincing, seasoning – these tasks take as long as they take, whether completed now or later.

Process time includes tasks that can be completed without the chef’s direct attention. Grilling, heating, marinating, boiling – these are processes that have to be started by a human, but continue to happen even when the chef turns his attention elsewhere.

Unlike immersive time, process time is highly sensitive to when it gets started. If I don’t start cooking the rice now, and wait to start it until I need it, I might have to sit around and wait for 15 minutes for it to finish. A minute to start the rice cooking now is worth 15 minutes later on, because the rice will use all the time in between to finish cooking.

In knowledge work we barely recognize the difference between immersive and process time. We actually tend to overvalue immersive time (sometimes called “deep work”), because that is when it feels like we are doing our best, most important work.

But it is actually process time that offers us the most leverage. Because the small actions we take to kick off process time unlock the efforts of others on our behalf.

If I don’t take 20 minutes now to train a colleague in how to complete a task, and instead train them next week, that is a whole week they could have spent performing that task on my behalf. If I don’t send a direct report an email now to schedule the next project check-in, and wait until next month, that is a whole month they could have spent thinking about and preparing for it.

These might not seem like especially important actions. They take mere seconds or minutes. Yet when you consider the potential of the larger network you are a part of – your friendships, your team, your organization, your community – the ability to leverage their abilities will always far, far outweigh what you can accomplish on your own.

There’s no distinction more important for the items on your to-do list than which tasks require immersive time, and which require process time. Training yourself to distinguish between them is crucial to being able to consistently make first moves, because process work is most effective when it happens early.

4 – Finishing mindset

In cooking, a dish that is 99% finished has zero value.

Chefs don’t get partial credit – either the dish is finished, steaming hot, delivered to a hungry customer, or it is worth nothing and goes into the trash.

Because of this brutal reality, chefs must adopt a “finishing mindset.” They loathe the incomplete. They don’t start what they can’t finish. As they start making a dish, the chef is determined to see it through to completion, because they know that the failure to do so will render all the effort that went into it worthless.

On the other hand, once the chef finishes a plate, a tremendous amount of value is instantly unlocked. And not just because the customer now has their food. Finishing actions clear the mind – a finished plate does not require ongoing attention or memory. In contrast, when unfinished tasks are allowed to accumulate, they clutter the mind and make even the task you’re focused on difficult to complete.

The same situation applies to knowledge work. It seems harmless to start and stop tasks as new information becomes available. But there is a hidden cost each time we do so. The unfinished task has to be managed and tracked and updated. It takes up space on your to-do list, on your computer or desk, and most importantly of all, in your subconscious mind.

These small frictions, multiplied by every unfinished task and accumulated over time, can eventually add up to an overwhelming burden that grinds your progress to a halt. You can actually reach the point where it takes all your bandwidth just to remember and track all the unfinished tasks, leaving no time left over to complete them. You have to run as hard as you can just to stand still.

To adopt a finishing mindset, ask yourself every time you start a project: “How and when will I finish this?” It’s about staying focused on the final deliverable and constantly tracking toward the expectations of the people you will be delivering to. It’s about making a plan not just for starting things, but for ending things. In the same way a pilot has a plan not only for taking off, but for landing.

You can’t always finish what you start, of course. Knowledge work is inherently unpredictable. Sometimes a quick phone call turns into an hour-long in-depth discussion that throws off your entire day. Or a piece of code you’re creating balloons into an all-consuming troubleshooting session.

Even in those cases, we can still follow a finishing mindset. Instead of dropping one task and turning to another, take a few extra seconds to tie up what you’re working on for later retrieval. Capture an open loop in your task manager, or highlight as you read so you’ll know exactly where you left off.

What you should avoid at all costs is “orphaned tasks.” These are tasks that continue to take up mental and physical space because they haven’t been tied up in the easiest possible form to be resumed later.

5 – Small, precise movements

You might think that, in order to deliver a steady stream of finished plates, a chef has to move as fast as possible. But that isn’t quite right. It’s more accurate to say that they move with “small, precise movements.”

Because each move is small, it doesn’t take much time. Because it’s precise, it has exactly the intended effect, without wasting unneeded time or effort. Small movements can be repeated quickly, which helps the body memorize the muscle movements and turn many of them into automatic habits. Repeated movements can be standardized and measured, which leads to further gains in efficiency.

Once each of these small, precise movements has been mastered and habituated, they can be put back together into a high-speed assembly line of delicious food. The chef eventually learns to work fast, but not because they are trying to work fast for its own sake. The speed comes from the accumulated efficiency in every step in their workflow.

As knowledge workers, we know how important it is to break down our projects into smaller parts in order to make them more feasible. But what is less appreciated is that it’s equally important to break down the repeated, habitual actions we take every day.

For example, “checking email” for most people is a vague, unwieldy, imprecise, and therefore slow and cumbersome movement. It’s never done the same way twice, which means no habits are formed, no efficiency is gained, and we don’t really improve at it over time. Despite the fact we’ve probably spent many hundreds of hours cumulatively checking email.

Instead, we should break down the actions we take most often into their constituent parts, such as in my checklists for doing a Weekly Review or summarizing a book I’m reading. Rather than leaving it to chance, I follow a process, which gets slightly better and faster (members-only article) every time I use it. Once I know the necessary steps, I can also outsource or automate them.

In the modern economy we are taught that speed is antithetical to quality. Excellence is supposed to require long, slow, deliberate thought. But for a chef, speed is an essential component of quality. An otherwise perfect dish 5 minutes too late isn’t perfect.

Until we deliver, there has been no value created, no lessons learned, no feedback received, and no improvement realized. Being able to compress time and deliver sooner is thus an essential part of the feedback loop that leads to true quality.

6 – Arrangement

The main source of outside intelligence a chef has to draw on is physical space.

You might not normally think of physical space as “intelligent.” But space can remember things, remind you of things, and track things to completion. Being able to utilize space is powerful because, unlike keeping an idea in your mind, keeping an item on the counter uses no energy. It is “free” intelligence that we as humans are uniquely equipped to take advantage of.

A chef will arrange her workspace to reflect the movement of food. Unprocessed ingredients move in from the left side of the cutting board, cutting happens in the center, and processed ingredients move to the right. Knife and towel go back to their designated places after every use.

This “zoning out” of ingredients and tools needs to be constant from day to day, so that the chef can internalize where everything is located and how it moves. The workspace becomes like an extension of the chef’s mind, so she can reach for a spoon or knife just as intuitively and naturally as she reaches for a thought in her mind.

As knowledge workers, our working environment is changing all the time. This has even been touted as a major benefit of remote work – that we can do it from anywhere, at any time. But there is a hidden downside: we don’t get the opportunity to internalize our workspace and master the space in which we move.

But in another sense, our working environment is extremely stable: it happens on our computer, which can be thought of as a virtual staging area that extends past the edges of our screens to our mobile devices, tablets, smart watches, and even the screens of others.

It’s up to us to curate, design, and arrange our virtual workspaces to provide the predictability that our work inherently lacks. This can be as simple as:

- Creating a “start up” and “wind down” routine to begin and end your day predictably

- Adopting a digital notes app as your main productivity tool (which I call a Second Brain), so you always have all your content with you

- Creating dedicated workspaces for each of your most important projects (such as in my PARA Method)

- Finishing each day or week with “Desktop Zero,” closing all your browser tabs (after saving them in a Read Later app), and shutting down your computer (a parallel to the neutral stance, or “zero point,” that chefs seek to consistently return to).

Each of these routines create boundaries – of time, space, or intention – around the states of mind that you want to protect and promote in your life. The boundaries tell you what you should be focusing on, and just as importantly, what you should ignore.

Honesty at work

At the heart of mise-en-place is an unrelenting honesty about the limits of time and space.

Chefs work at the razor’s edge, balanced precariously between speed and quality. They receive instantaneous feedback the moment they make a mistake. They can’t tell themselves stories such as “The project is on track” or “I’m waiting on someone else” or “I’ll get to that soon.” The work comes in waves, and there is only time to navigate those waves, not explain or analyze what they mean.

To succeed in this situation, chefs develop an ability that is also our goal as knowledge workers: to be focused and at the same time aware of the big picture. The chef’s ethos is total utilization: to use every part of the animal, every minute of time, and every layer of their awareness in pursuit of excellence.

Thank you to Sashi Sabaratnam McEntee, Vishnu Agnihotri, and Noorsimar Singh for their suggestions and feedback on this piece.

Follow us for the latest updates and insights around productivity and Building a Second Brain on Twitter, Facebook, Instagram, LinkedIn, and YouTube. And if you’re ready to start building your Second Brain, get the book and learn the proven method to organize your digital life and unlock your creative potential.

- POSTED IN: Attention, Book summary, Building a Second Brain, Flow, Habits, Organizing, Workflow